This post is also available in:

日本語 (Japanese)

by Yasuko Kasaki | Jan 2, 2026 | Art

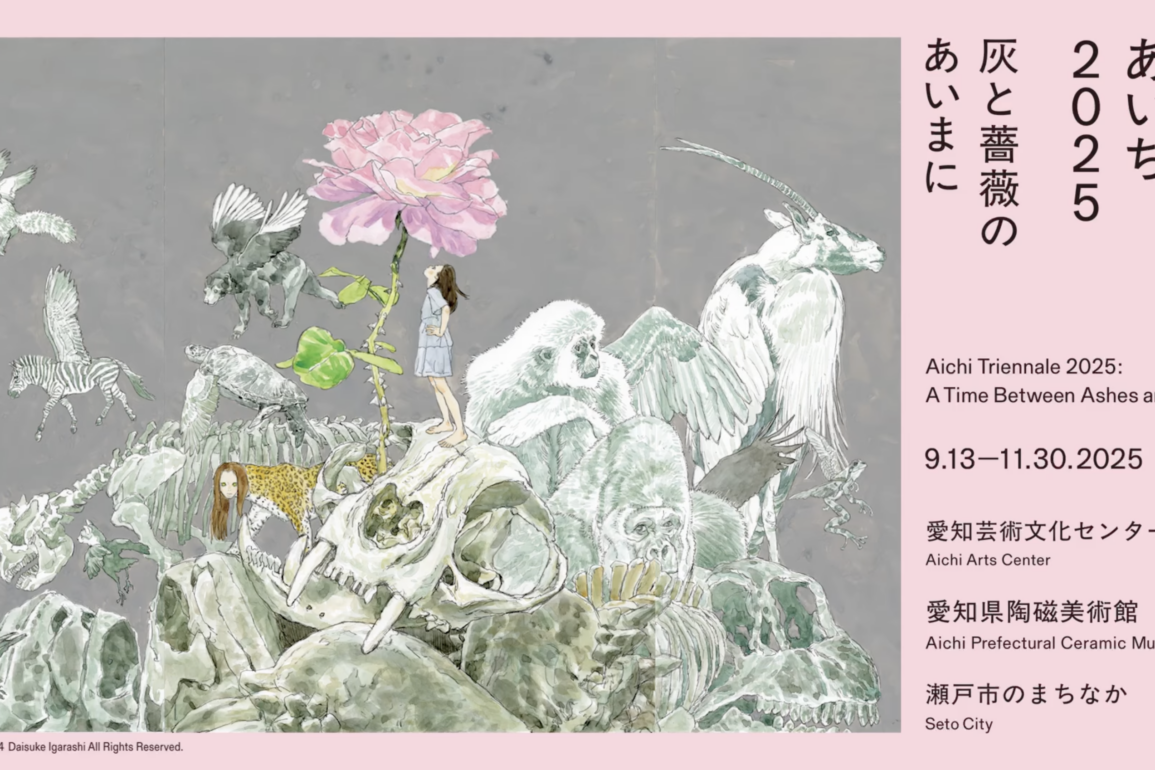

During my autumn stay in Japan, two compelling reasons drew me to the Aichi Triennale, which brought together a diverse group of non-Western artists/groups, including participants from the Middle East, Africa, and Latin America, alongside Asian artists/groups, with twenty-six from Japan, and took place in the Aichi Arts Center and Aichi Prefectural Ceramic Museum in Seto City, Japan from Sept 13 to Nov 30, 2025.

The first was the resonance of its 2025 theme, “A Time Between Roses and Ashes.” At first, I misread the Japanese phrasing—not aima ni but awai ni, a slippage that unexpectedly deepened my engagement. While both signify “between,” awai, written in hiragana, evokes a liminal, unstable interval—neither fixed nor resolved. That fragility of meaning felt less like a mistake than an entry point: a clue to how this Triennale positions itself within uncertainty, translation, and historical fracture.

The Japanese sensitivity of rendering “between” as awai—written in hiragana, suggesting an indeterminate, liminal space—felt as though it had already, quietly, articulated the entire spirit of the Triennale. Of course, aima carries much the same meaning, but it was precisely this wavering, this instability of reading, that seemed to form the very core of the project.

The second reason was discovering that the title had been taken from a poem written by Syrian poet Adonis (Ali Ahmad Said) in response to the 1967 Six-Day War in the Middle East. I wanted to see how a theme originating from that historical moment would unfold in Japan. Alongside anticipation, I carried a measure of doubt—and holding both, I felt a strong need to witness the exhibition for myself.

It was the Six-Day War that prompted conceptual artist Yoshiko Chuma to leave Japan with the conviction that she could not remain where she was and must move to New York. To this day, she has consistently addressed the Palestinian struggle—not only that, but conflicts and margins across the globe—through dance performance, even dancing together with Palestinian collaborators. Among the people around me, she is the only Japanese artist I know who continues to take that point of origin so seriously, so bodily.

Now, the generation that experienced 1967 firsthand is no longer the majority. And yet, in recent years, there has been a noticeable increase in Japan of people turning their attention toward Middle Eastern issues, gradually recognizing them not as “someone else’s problem,” but as a matter that belongs to the world—and to each of us individually. How, in such a present-day Japan, would this Triennale be opened, seen, and received? That was the question at the heart of my interest.

I deliberately avoided researching the exhibition in advance. But by the time I had encountered the first work near the entrance and stepped into the next gallery, I already felt overwhelmed: there was not enough time, the scale of the Triennale was immense, the number of artists I wanted to encounter was staggering—and above all, a sense of astonishment toward the exhibition’s curator rose in my chest.

Who on earth is this person?

Her name is Hoor Al Qasimi, an Arab curator born in 1980. From my perspective, she belongs to a younger generation, yet as a curator, she brings remarkable experience and composure. The executive committee that appointed her and worked alongside her to realize this exhibition has, in my view, achieved a clear success—both in the way the theme is presented, and in how the question of what art can do is offered with open, outstretched hands. Equally, they have succeeded in carefully gathering voices from the world’s margins. For this, I wish to offer heartfelt applause and gratitude.

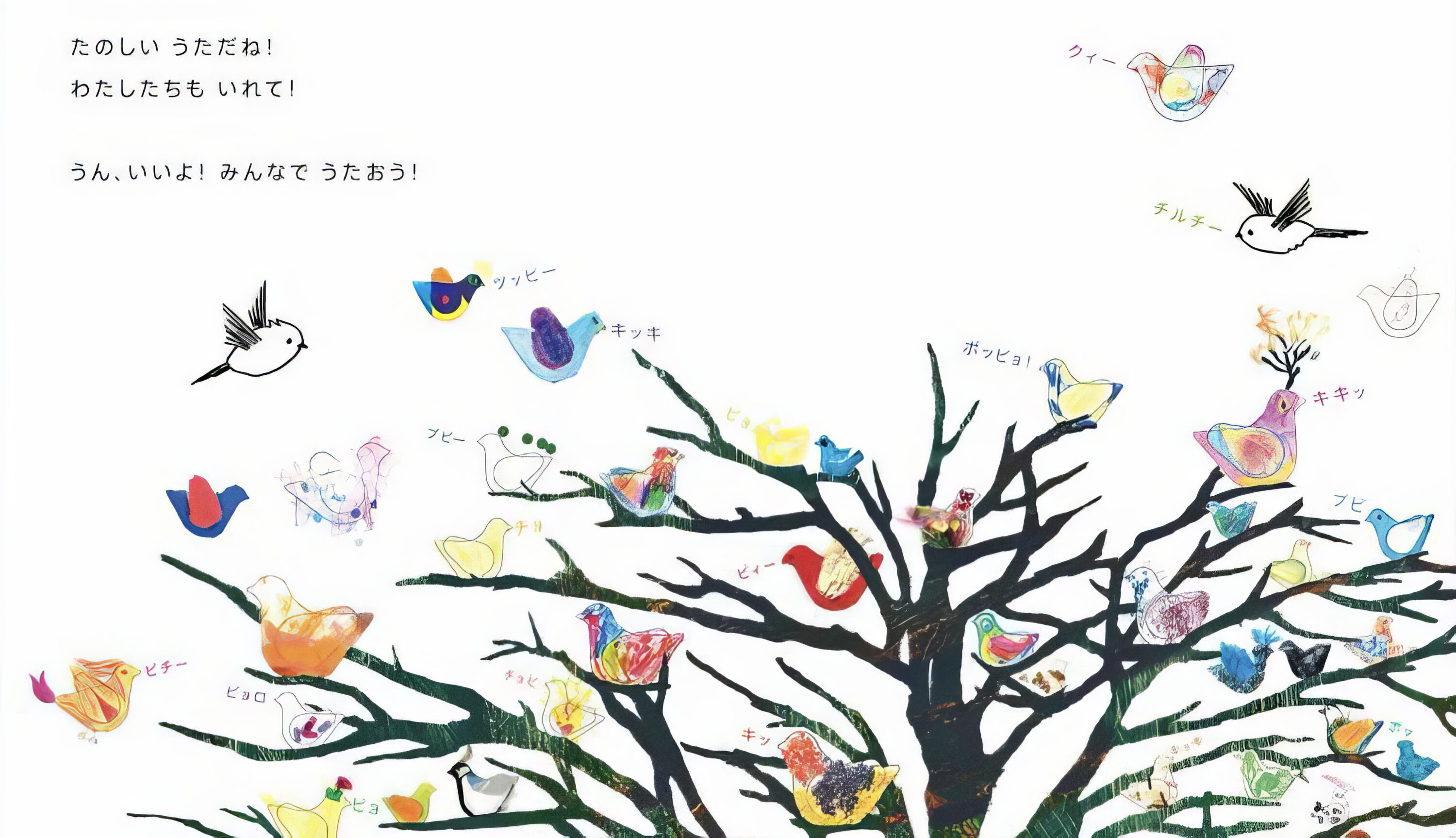

Those marginal voices came from everywhere: from the ocean floor, from forests, from bombed battlefields, from lives that have endured labor upon labor, from the histories of Indigenous peoples pushed aside, relegated to the periphery.

They were not shouts, but whispers. As I moved from one gallery to another, those whispers continued to lightly vibrate my eardrums, coming from the side, without interruption. Surrounded by them, I hurried forward—there was no time, I wanted to see everything, half a day was nowhere near enough—yet at the same time, I felt the ground beneath my feet gradually soften, becoming rich and yielding.

Perhaps it could be described as the force of life rising up from below. The voices may not have come only from beside me, but also from underfoot. Within them, at moments, I sensed the trembling of the Ainu, the sobbing of the Tamil people.

Battlefields turned to ash, bodies turned to ash, forests and coral reefs turned to ash. And we ourselves, enclosed within a gilded monetary society, are already turning to ash while pretending not to notice. Rather than confronting these realities head-on in combat, something else emerged—as if from another dimension—overflowing with the softness of life and a resonant joy. Gradually, my own body felt as though it, too, was becoming a resident of that resonance.

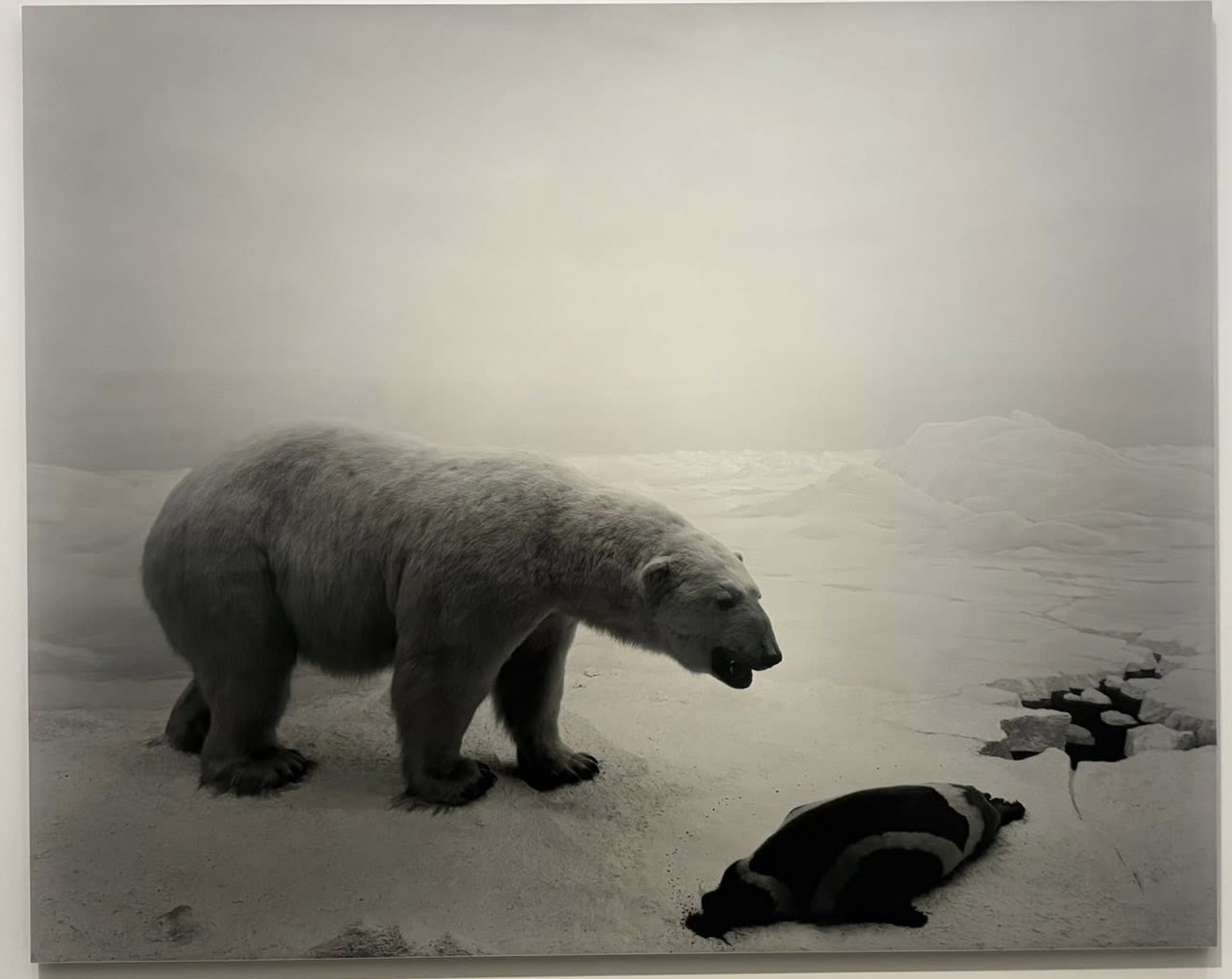

Standing before a work by Hiroshi Sugimoto, a polar bear within the piece spoke to me—also in a whisper.

“Yes,” it said.

“Yes, the world has indeed already ended.”

“And now, you are experiencing a Renaissance.”

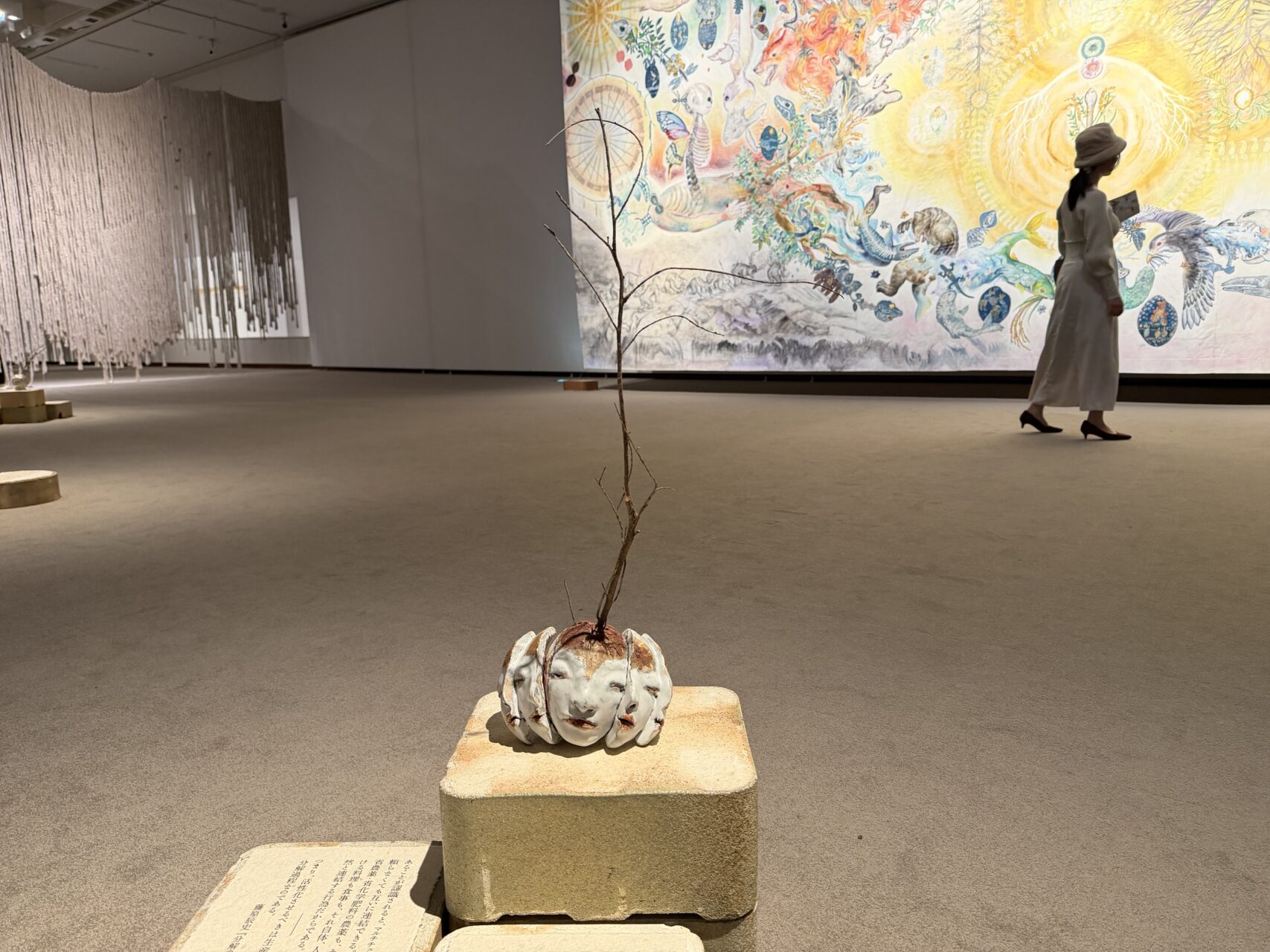

Those words became real for me, most powerfully, in the exhibition space of Maki Ohkojima. The large room was filled with low, murmuring whispers that seemed to crawl up from the depths of the earth, but what overwhelmed me most was a single, monumental painting and installation: “Tomorrow’s Harvest” 2017–18.

Viewing it was an intensely personal, overwhelming experience—one that immediately communicates itself as childbirth—how could such a force expand so delicately, so softly, as pure harmony, into earth and forests, countless organisms and microorganisms, water and its flows and surges, even into the atmosphere itself? Restrained yellows form expanding circles, red receives them, and Pegasus carries golden ears of rice up toward the heavens. Numerous small installations are positioned throughout the large room, depicting or referencing another multitude of orgagnisms and environments. In one, a suffering human figure is depicted, literally bleeding as it grasps a single grain of rice—only to have even that taken away.

It was as if the painting was quietly addressing the viewer.

What does it say?

“Even so, this is reality.”

Suffering itself is not reality. Rather, even at the depths of suffering, reality may be enveloped by a beauty and power of this magnitude. Life is not something fixed, but a surge, a swelling movement.

The exhibition notes state that the work “depicts the symphony of organisms forming relationships in which they live through the seasons together, eating and being eaten” to convey the theme that life “circulates in a distorted way, becoming entangled, tangling, and unraveling.” Ohkojima has participated in residencies in India, Poland, China, Mexico, France, and other countries, collaborating with scientists to observe ecosystems and create art that “expresses the complex processes of life and death.”

“In 2023, she formed an art unit with Tsuji Yosuke under the name ‘Ohkojima Maki.’ Employing a variety of artistic media, the unit portrays the dynamic response of life on a planetary timescale over billions of years. In addition to motifs pertaining to the global environment, like forests or the land, volcanoes, oceans, minerals, and mud, the art of Ohkojima Maki contains motifs such as birds, snakes, whales, slime mold, primates, deer, chimeras, and embryos. Through images of life going through a continuous cycle of intermingling, viewers can sense the artist’s imagined landscape, which empathizes with the perspective of diverse environments and the other, continually transforming into something more than human.”