This post is also available in:

English (英語)

by Christopher Pelham | Jan 26, 2026 | Art

The creations of Japanese artist Mariko Mori, a respected and well-known figure in the international art world since the 1990s, have never seemed more present, needed, and timely than now. Why? In an era saturated with stimuli, her work invites us to slow down, suspend our assumptions, and enter a quieter relationship with ourselves, one another, and the world. Her art calls us back to what she simply names Radiance, the light and interconnectedness that underlie everything.

In the past fifteen months, I have encountered her works in Arles, Venice, Osaka, and now once more in New York, where her third solo exhibition, Radiance, opened at Sean Kelly on October 30. These encounters—and a conversation with her recently over Zoom—confirmed a sense I first felt years ago: that her art is not merely timely and delightful; it is a vehicle for healing.

Encountering Radiance at Sean Kelly

Entering the gallery, we first encounter a jaw-dropping pair of sculptures: two vertically oriented, rounded forms shimmering with reflections and pastel colors: violets and pinks with splashes of blues, greens, yellows, and orange. Visitors slowly circle the pair, captivated by their ever-changing hues. These objects seem to contain a vast world within. Or maybe they are portals. I wondered whether they represented cairns or monuments of some kind, or an advanced, benevolent intelligence. Let’s see what they are called. Love II (2025). Surely, they are meant to feel friendly! They certainly radiate friendliness, curiosity, and a subtle sense of welcome.

The gallery notes say these works reimagine Japan’s revered rocks, or Iwakura, which have been considered sites of divine presence for millennia. “Their dichroic surfaces shift with ambient light and the viewer’s movement, reimagining invisible energies that recall the stones’ original function as portals to the sacred.” Ah, they are meant to evoke totems and portals!

Mori draws on the Kojiki, Japan’s oldest creation text, in which early deities exist as pure forces before emerging in pairs such as Izanagi and Izanami. Without this context, viewers might not guess the mythology—but they do feel the pairing: a gentle affection between the two forms, a quiet conversation of color and presence. The work is less about mythological characters than about what they represent: creation, interconnection, and the playful, curious energy that binds all things.

In the next room, Shrine (2025) invites visitors to remove their shoes before entering a veil-lined chamber containing two more acrylic stones on a raised white platform. These stones, one slender and upright, the other grounded and faceted, face each other across a glowing circle carved into the floor.

Stepping inside, I am gently stopped by a member of the gallery staff, who informs me that visitors must remove shoes before entering, just as we do when entering Japanese temple buildings. Once inside, I realize a gentle breeze is blowing, as if an invisible spirit is inhabiting the space. The circle is carved into the floor and lit from within the cavity, presumably by LED, and it calls to visitors as much as the sculptures do. Standing within that circle, I felt a balance—an interplay of receptive and assertive energies.

The installation, all in white, evokes purity, breath, and stillness. It channels the experience of entering a Shinto shrine while using materials and forms that unmistakably belong to the future. This simultaneous ancientness and futurity is one of Mori’s signatures: she builds new forms to express ancient truths.

Along the gallery walls, her Unity and Genesis works—circular photo-paintings rendered through 3D computer graphics and UV-cured pigments—pulse softly like celestial bodies. Pastel “starbursts” echo sacred geometry, the cycle of creation, and the infinite play of light. Whether or not one knows the Kojiki deity Amano Nakanushi no Kami (the “invisible light” that she says inspired the series), the paintings evoke that same sense of boundless, gentle presence.

One can imagine that Mariko herself must be aligned with the universe and universal love during her creative process, patiently experimenting and iterating until arriving at deceptively simple images that so purely embody her vision. She shared one such experience that guided her hand: “the manifestation of a profound and boundless love—the primordial source from which all life arises… In that sacred moment, I felt a profound connection to the Great Light. My heart overflowed with the realization that no soul is ever truly alone.” Sitting with these works and reflecting on what she experienced while creating them, I felt deeply in harmony with her vision.

These works prepare us for the central theme running through Mariko’s practice: Radiance as the visible expression of Oneness. Playfulness is her method, intuition her guide, experiment her language.

Why Mariko’s Mediums Are So Contemporary

I wondered why Mariko renders deeply ancient, spiritual ideas using contemporary materials like layered acrylic, dichroic coatings, and UV-processed pigment. Her aim is not to modernize spirituality but to create forms that can genuinely be felt today. Moreover, she genuinely loves researching and experimenting and believes this experimentation enlivens the creative process and opens it up to helpful accidents.

Playfulness and Intuition

Mariko’s intuition and playfulness have shaped her creative process from the beginning. As a young woman, she was drawn to fashion for its creative freedom. Fashion led to modeling, modeling led to image-making, and image-making led her to continue her education in London, where a required course introduced her to the fine art world. There, she realized that art offered even more possibilities than fashion. Free to create anything she could imagine, she learned to experiment and iterate until achieving the desired metaphysical energy in her work. Creativity, she learned, emerges from play, not force; from intuition, not obligation. This same principle is at the heart of Radiance.

Visions of Light and the Turn Toward Oneness

I asked her to elaborate on how her spiritual practice and its influence on her work evolved and manifested. She said in the late 1990s, while researching the Buddhist Mind-Only (Yogācāra) school for the work Dream Temple, Mariko experienced her first profound spiritual vision:

“One day, I had a metaphysical experience: I was surrounded by many souls floating in the air, revolving around a very strong light. They were radiating. Unlike us, these souls didn’t have an ego – a gravity that the body has on the spirit. All of them were considered as one, as a whole. I realized that this must be the world after being liberated from the ego. In regard to these metaphysical ideas, it was a mind-opening experience for me.” — (HypeArt)

This was the moment she “opened a new chapter.” Art was no longer just freedom—it became purpose. Thereafter, she sought to align her life and work with these visions, and she was investigating how.

Her second significant spiritual experience came after completing her ambitious Wave UFO project in 2003. Feeling emptied, she followed an impulse to visit Okinawa, and there encountered indigenous priestess traditions and sacred sites that resonated with her earlier visions. This intuition-led journey helped her better understand her spiritual path and how it could guide her art-making, and later inspired her to found the Faou Foundation, devoted to creating site-specific monuments on six continents, beginning with Primal Rhythm, erected in Seven Light Bay of Miyako Island in Okinawa in 2011. It then led her to build a home/studio on the island, itself a work of art, and to discover various ancient monuments and ongoing indigenous practices there.

Still later, after installing a monumental Ring in Brazil, she again felt emptied—and again encountered the “strong light.” She realized:

“My creativity is inherited from the source.”

In these moments of emptiness, she says, new forms come.

“Every time I produce a large work, that’s what happens. I become quite blank and empty, and then I encounter this strong light again,” which reminds her who she is and inspires her next creative steps.

Mariko’s experience echoes what Patti Smith shares in her new memoir, Bread of Angels, recounting a time when she also felt emptied, devoid of inspiration. “I was just looking out at the bay, and it’s sort of circular, and I was receptive, and I was given. I was given the words to start the book.” When we meet that sense of emptiness with softness and curiosity, receptiveness, rather than “trying” to think of an idea, we open up enough space in our consciousness for new inspiration to enter.

Miracle-Mindedness and the Creative Process

Mariko’s creative method is grounded in receptivity.

“The light doesn’t tell me what to produce,” she says. “I tried to ask, but the light told me to enjoy the creative process.”

Instead, her ideas arrive through research, contemplation, dreams, and playful experimentation fueled by her visions.

She describes her collaborations not as engineering challenges but as joyful encounters:

“When you’re doing something new, it’s exciting. And something unexpected always happens—some kind of gift.”

A lot of her work requires collaboration with other people. She says, “I always found a way to meet the right person to collaborate with, and that’s really fun. It doesn’t happen all the time, but it’s wonderful when it happens.”

Similarly, she says that during her frequent travels, she also welcomes the unexpected. “You meet people and are guided by others, and you witness this golden path, especially for our project. It’s so unknown, so unpredictable, but I have a sense of trust, and that leads me, and I’m always excited to see what’s going to happen next. So, discovering a new world, new people, new cultures, is very interesting, very exciting. And I learn so much from new experiences.”

Her intuition, she believes, is to remain open to these gifts. If she creates without inspiration, the work feels “empty.” But when she in tune, the work becomes “a collaboration with a higher energy,” or, as she termed it in a 2008 interview with White Hot Magazine, a miracle.

If she creates without inspiration, the work feels empty.

“When somebody asks me to make something similar to what I did before, I always make undesirable work. I learned that when I was in my 20s. So I don’t want to make the same mistake again. So I’m very careful about that. Basically, the motivation has to be pure, has to come from your heart, and so one of the reasons that I don’t want to make purely commercial artworks often is because I’m afraid of creating something that is too much contrived, with no soul in it, an empty work.”

That’s a great lesson for us all.

This miracle-mindedness appears not only in her process but in many of her works like Miracle (2001) and Peace Crystal (2024), both of which I had the opportunity to see in person last year. Both works were inspired by visions, and both invite viewers into meditations on unity and universal origin.

I encountered Miracle in a group exhibition last year at the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh Arles, Van Gogh and the Stars. It consisted of 165 works by more than 76 artists—including Edvard Munch, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Yves Klein, to name a few—in conversation with Van Gogh’s Starry Night Over the Rhône (incidentally, the first time the beloved painting has returned to Arles since Van Gogh painted it there).

Miracle includes a series of round cibachrome prints evoking the cosmos with an installation in the middle of the room consisting of a crystal hanging over a circular pile of salt and glass bubbles. Perhaps more than any other work in this impressive exhibition, Miracle echoes what I feel is most meaningful in Van Gogh’s work, which is his sense of the miraculous all around him, his great love for whatever he perceived, his sense of connection. Gazing up at the stars, contemplating the infinite expanse of the universe, we can feel tiny and insignificant, or we can feel a sense of awe, affinity, and interconnectedness.

The works of Mariko and Van Gogh both call to mind the famous Rumi poem about interconnectedness that begins, “You are the drop, and the ocean.” They remind us that what we are, what life is, is inherently miraculous, beautiful, awe-inspiring, and all one.

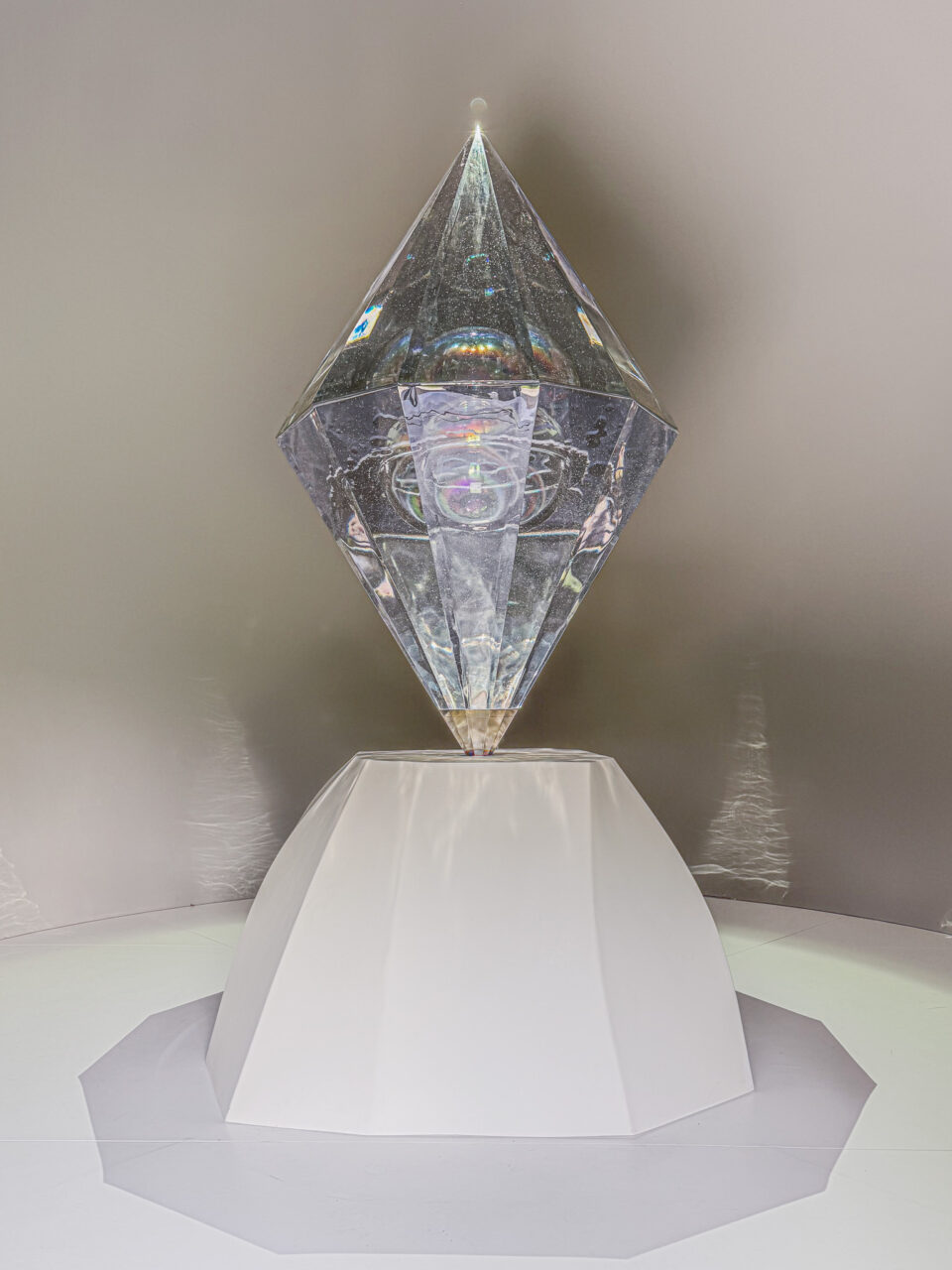

Similarly, Mariko’s Peace Crystal, which I saw during the 2024 Venice Biennale in the private garden of the Palazzo Corner della Ca’ Granda, also originated with a miracle. Housed in a pearlescent, tear-drop-shaped structure visible from Venice’s Grand Canal, the Peace Crystal looks like two diamond pyramids stuck together at their bases, pointing up and down.

At first glance, it appears merely decorative, a large and beautiful gemstone. But a closer look reveals a transparent sphere suspended in the middle. Contemplating the sphere, I realized that the Peace Crystal’s energy, which at first seemed only focused outward through the points, was actually also drawing energy inward, focusing and coalescing it into the perfect sphere balanced within. The energy is flowing in and out harmoniously. Or rather, the separation between in and out, inside and out, vanishes. The crystal operates as a meditative aid, catching the attention with its brilliant beauty and then focusing the mind’s attention until we notice and contemplate the sphere and the feelings of Oneness this both represents and engenders.

The exhibition notes describe the miracle that led Mariko to the creation of the Peace Crystal:

“Mariko Mori visited South Africa in 2015 based on her intuition to look for caves, although at the time she did not know why. Upon her return, while meditating, she thought of the caves. At that moment, the image of Peace Crystal appeared in her mind: two cones, top and bottom, linked to contain a sphere. The sphere radiates in full-spectrum colors, symbolizing the soul. The two cones, top and bottom, represent the upright body of humankind, serving as a capsule to hold the spherical soul. …Mori came to understand that the sculpture symbolizes upright posture, which was essential for human evolution. …The artwork reminds us of our common origins and that we all belong to one family tree, uniting individuals throughout the world to deepen our understanding of our shared humanity.“

In a way, Mariko’s theme perfectly embodied the theme of the Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere (Stranieri Ovunque). Chosen by curator Adriano Pedrosa to highlight artists from diverse and marginalized backgrounds, the theme was meant to convey “that foreigners, migrants, and outsiders are everywhere in the world, and it also suggests that everyone is a foreigner in some way, ‘even to ourselves,’” meaning that we all have something in common. We are all connected, united, in part, by our experience of being strangers in a strange land. Mariko’s Peace Crystal not only engenders an experience of connection with other people all over the world, but it also affirms our connection to others throughout history. Eventually, she intends for the Peace Crystal to be permanently installed at a site within Ethiopia as a monument to the “cradle of humanity.”

Okinawa, the Cave, and the Shrine

Mori now spends part of each year in Yuputira House, the home she built overlooking the sea on Miyako Island, a place steeped in indigenous spiritual traditions. All white and curvy, a reflection of the smooth coral found there, Yuputira House provides Miyako with an ideal setting for contemplation, creation, and connection to nature.

Beneath the house, she discovered a small cave containing two nature deities—one male, one female. Mori visits to offer gratitude whenever she arrives or leaves. The experience of their paired energies seeded the structure at the heart of her Sean Kelly exhibition:

“The Shrine came from that cave. The male and female energies—the pair—became the idea.”

This is why the exhibition begins with Love II, another pair. Oneness, expressed through twoness, radiance expressed through relationship—that is her language.

Motherhood and the Continuation of Play

Motherhood entered her life as another surprise. At first overwhelming and challenging , it soon revealed itself as a new creative source. In fact, when her daughter, Manna, was still inside her, she started to draw. “And I felt that the energy to draw is not from me. It’s not mine. [It’s from her.] And after she was born, I had to hug her and hold her all the time. I made a work called Oneness [a sculpture of six aliens in a circle holding hands]. The audience is welcomed to hug the aliens and the audience will feel the heartbeat from it. Manna is like an inspirational source.”

Manna has since appeared in many of her mother’s ritual performances. “She started very young, doing it like a family business.”

Because Manna grew up deeply exposed to art, Mariko and her husband decided that Manna should attend an academic university and try different things.

“When you are young, you have to try different things as much as possible to find something that you really, really like, so you lose all sense of time and life becomes joyful, because life is quite long when you do things you don’t like.”

Although speaking of Manna, Mariko could be describing her own path, which Manna is now following anyway. Manna has begun working with the fashion organization Midnight Runway and designing her own jewelry.

Art as a Practice of Radiance

By following intuition, play, and inner guidance, Mori has created not only a remarkable body of work but an expanded way of seeing. Her sculptures and paintings ask us to pause, attune, and allow ourselves to be moved by the invisible currents that bind us—across cultures, across time, across the illusion of separateness.

And she reminds us that this capacity is not hers alone.

“Creating things is the true nature of humans. If you stop creating things, you are no longer using the strongest ability of your being. It’s a fundamental act. There is nothing more connected to the soul than art” (Louisiana Channel documentary, 2023).

Mariko’s statements about creativity being central to our identity echo many spiritual texts throughout history. For example:

“The Self desired: ‘May I create.’” (Taittiriya Upanishad 2.6)

“The soul must create; it cannot remain without bringing forth.” (Plotinus, Ennead V, Tractate 1)

“Imagination is not a state: it is the human existence itself.” (William Blake)

“The whole universe is imagination, and he who knows himself knows that he is imagination.” (Ibn ‘Arabi, Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya II.313.5)

“Your function is creation.” (A Course in Miracles, T-7.I.3:3).

We participate in creation whenever we look closely, soften, or let beauty shift something within us. Creative attention is an act of love. In a world awash with noise, the simple willingness to see clearly is itself a form of artistry. In fact, it takes real effort to resist.

As Mariko’s Radiance reminds us, we are beings of light and connection. To witness that in her work—and in one another—is itself a creative act. Radiance is our nature. Let’s be happy witnesses of it.

Next October, the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, in collaboration with the Asian Art Initiative of the Guggenheim Museum New York, will open a major retrospective of her work.

You can follow Mariko online at: