This post is also available in:

日本語 (Japanese)

Sept 11, 2025 | Music

Sylvester “Sly Stone” Stewart died on June 9th, 2025. There have been a lot of narratives about his life and death, but only a few came from him directly. What is easy to say is that he was one of the three chief architects of funk, along with James Brown and George Clinton. Unlike Brown & Clinton, who were brilliant leaders and performers but not musicians, Sly Stone was a musical prodigy. His talent was encouraged by his family and his church, and he mastered piano, guitar, bass, and drums at a very young age. The only modern musician with his influence and skill set was Prince, and it was obvious that he drew a great deal of inspiration from Sly.

So did George Clinton. So did a lot of other bands. Clinton, a musical chameleon who absorbed multiple influences, was fascinated by how Sly seamlessly incorporated gospel, R&B, pop, and rock in his multiracial and multigender band, Sly & the Family Stone. Growing up in the Bay Area of San Francisco, this kind of multicultural blend was not unusual for him or the area. Sly paid his dues doing session work and pick-up gigs, along with his memorable stints as a DJ and a producer. When his band hit it big in 1969 with multiple top-ten hits, it was mostly with upbeat, cheery songs like “Everyday People,” “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” and “Everybody Is a Star.” There was social commentary as well, but it all felt in line with the dissident but utopian hippie movement of the late 60s.

As I said earlier, there are a lot of narratives about the band and Sly, and precious few are from the man himself. This essay isn’t about relitigating history or assigning blame. Suffice it to say that it was clear that the band’s success put a lot of pressure on Sly and led to fractures with bandmembers Larry Graham and Greg Errico, among others, though those two left the group after their seminal album, There’s a Riot Goin’ On!

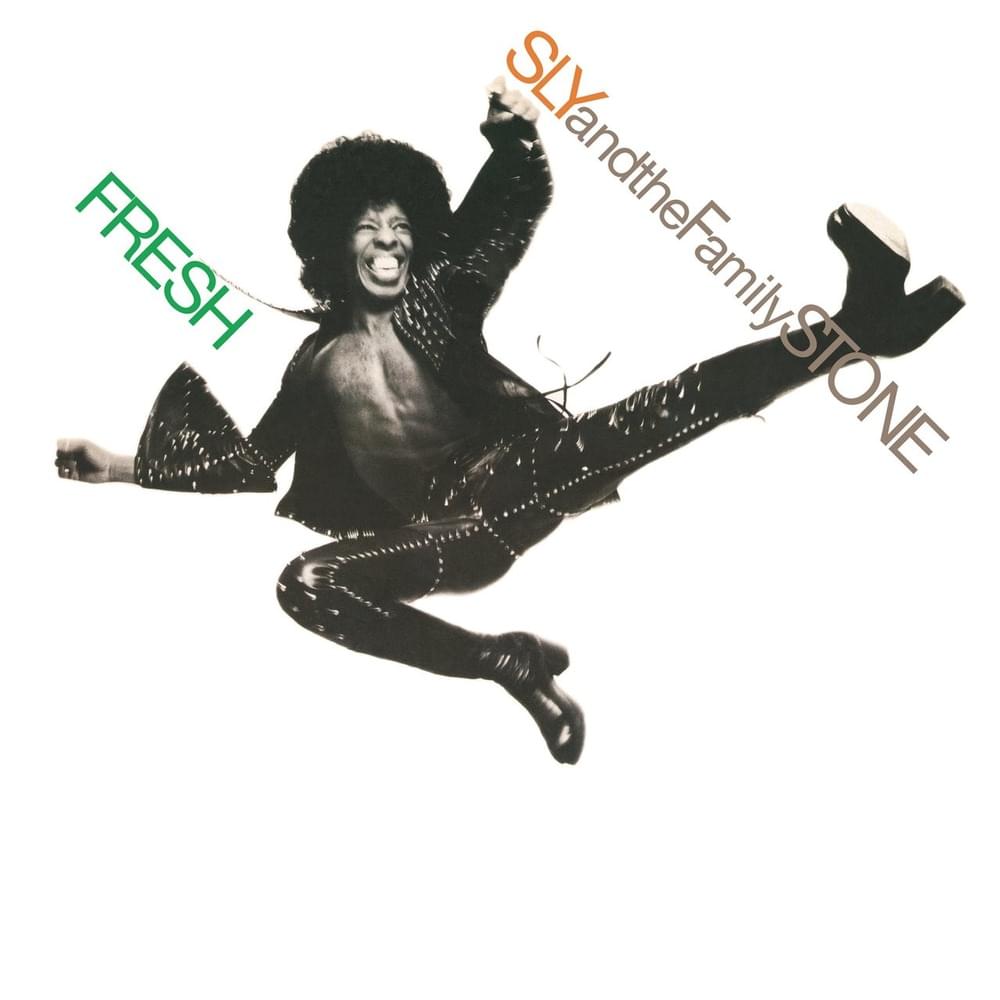

In recent years, there have been books and documentaries about Sly. Most recently, the very good documentary Sly Lives! (aka the Burden of Black Genius) (directed by Questlove) raised a number of important questions, especially regarding race. However, in that documentary, as well as the book Sly & the Family Stone: An Oral History, the actual discussion of the music tails off after their Woodstock concert of 1969. There is lip service given to Riot and the 1970 earth-shaking funk of “Thank You (Falletinme Be Mice Elf Agin),” but what I consider to be his greatest achievement, 1973’s Fresh, barely gets a mention.

The personal turmoil of the band and the multiple personal agendas have seemingly eclipsed what is actually the most important thing: the music. With Riot, Sly completely altered how the band recorded songs. What had been a joyful collaboration had run its course, and Sly used one of the early drum machines to record demos. Only later did he add musicians to fill in what he needed. Sly & the Family Stone had almost entirely become Sly’s vision from top to bottom. It’s unsurprising that the other musicians would feel a certain way about this, but Sly completely reinvented funk in a way that was both highly influential and impossible to duplicate.

Riot has a bitter, jaded, and apocalyptic feel. One could almost sense the musical and personal struggle on the record. It took Sly two years to produce Fresh, once again building almost the entire album from the ground up with his own demos and then adding in others when needed. It was still a family affair, as his sister Rose Stone was featured prominently, and his younger sister Vet was heard as part of the “Little Sister” vocal unit. True to its title, Fresh is lighter, more relaxed, and much more personal than any music Sly had written to date. It’s also much funkier, as Sly had in turn embraced the deep grooves of the Bootsy Collins-era JBs of James Brown.

Lyrically, the band’s lyrics previously were often written in the second person and were aspirational (“Stand, for the things you know are right”). There’s also a lot of direct commentary on race, diversity, love, and a better way of living. That all went out the window for Sly’s 70s material after he had achieved worldwide fame. It’s clear from both his reclusive lifestyle and the actual lyrics that the pressures of fame and success, coupled with the targeted breakdown of the civil rights movement, led to cynicism, despair, and a painful need to escape.

Fresh is his attempt to come to terms with all of that, while still maintaining the last vestiges of unity the band had left. Sly felt a need to reinvent the band’s sound, as the pop/rock/R&B fusion had run its course, and it was time for something dirtier and funkier. Fresh features songs that are much more on the “one” than a lot of his previous songs. That propulsive emphasis on the first beat (rather than the two and four) is the essence of funk as James Brown and his band created it. Funk is a musical genre based on the idea that the traditional rhythmic components of the band become the lead instruments (bass and drums in particular), and the traditional lead instruments have a more rhythmic role. There are many variations on this formula, and funk also proved to be versatile in taking elements from gospel, blues, rock, soul, R&B, country, and psychedelia.

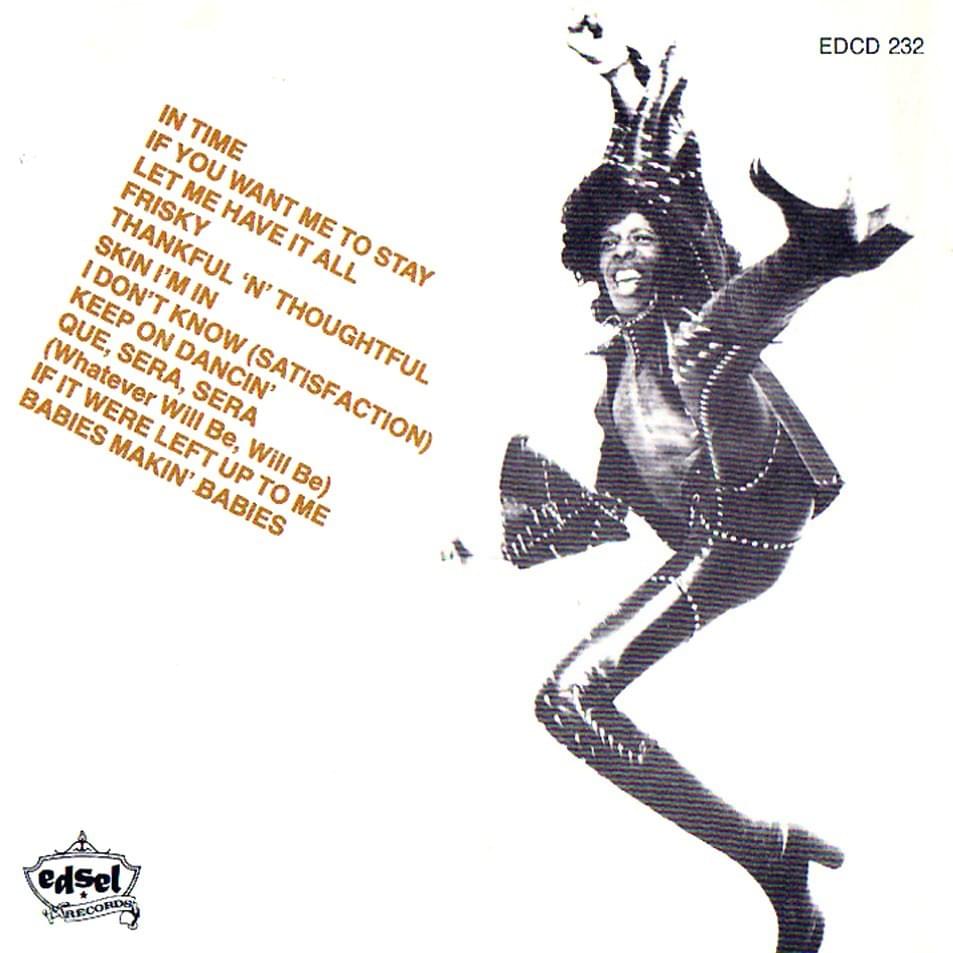

Fresh opens with “In Time,” a deeply complex song musically that starts with a simple, pre-programmed drum machine beat that suddenly becomes more complex when a high-hat drum starts to play around it, dancing playfully. There’s a lot of that counterpoint in the song, as Sly employs syncopation in a way rarely heard before in his music. He also doubles up guitar and electric piano at points to create a heavy sound, but the true star of the song is the aggressive bass playing. Larry Graham’s replacement, Rusty Allen, is credited with bass on the album, but it wouldn’t shock me if it was really all Sly. While the bass is a little buried in the mix, it is rewarding to zero in on it to enjoy the complexity of the bass as a lead instrument. It adds to the overall heaviness of the song. The horns blast in with the kind of shorter, punchier riffs that you might hear as a call-and-response on a James Brown song.

Sly’s voice is just as much an instrument as anything else, and it fits seamlessly into the overall aesthetic of the song. There are a lot of slurred notes on this song and record, meaning that one note flows into another without separation (also known as legato). This is a major departure from his earlier songs, where the notes were all distinct and punchy. His voice, the electric piano, and even the horns are all slurring notes to create that slightly distorted effect in the songs. Sly is the lead singer on most of the album, and there’s only one song that has the typical group singing that was characteristic of so many of their most popular hits. Sly, on those records, was often singing in and between other singers, as a sort of impish commenter. Here, his full range of techniques is on display: the growl, the falsetto, the screams, the mix of slurred lyrics and highly-enunciated words. The call-and-response with Little Sister, the backup singers, is straight out of church.

The lyrics seem to be gently mocking how long it took to make the record, but it’s also a commentary on how his life became “faster,” and how he chose to deliberately slow down everything. The chorus says, “Two years–too long to wait/two words, get it straight,” and those two words are “In Time.” Everything in time, even if it feels like he’s “procrasti—-nating.” Sly also seems to take shots at the bandmates that left with “And there’s a wreck yard in the mind of a quitter” and “Why give slack to a deserter?” Mostly, this is Sly’s declaration of his agency: “Oh I felt so good, I told the leader how to follow,” as the label would simply have to “Stay around, to get a show.” The complexity of the music is a statement of purpose that backs up the lyrics and his new method: “it’s worth the wait. This is better than anything I’ve done before. And I’m doing it mostly by myself.” All of this is also a declaration to his audience, as well.

The second song, “If You Want Me to Stay,” was Fresh‘s biggest hit and a staple of Sly’s live show at the time. Sly & the Family Stone toured extensively in 1973 and 1974 and also opened a lot of live shows for Parliament-Funkadelic in 1975–76. The opening bass part with a short repeating riff segues into the classic, deeply funky, walking bass part, with the jangly piano and Sly’s ethereal voice further conjuring it. After the bass walks, it resolves into a cymbal crash that kicks off the lyrics. The lyrics are accompanied by a repeating horn riff with descending notes that play off the descending notes of the walking bass part. The drum part is a simple shuffle that helps accentuate both Sly’s voice and his piano, which is the spotlighted instrument that gets a solo. The notes are less slurred on this song, as Sly chooses to carefully articulate most of the lyrics as well. There’s still the classic Sly growl and Sly scream, but there’s a reason why this was a big pop hit: it’s less challenging musically than some of the other songs on the record. Of course, it didn’t need to be complex with that funky all-timer of a bass groove.

Lyrically, the song feels deeply personal. It’s directly sung in the first person, and while the object of his query is unclear at first, he makes it obvious in the third verse: “You got to get it straight/How could I ever be late? When you’re my woman taking up my time?” This is a relationship song, and Sly is not kind here. Later, Sly relents, admitting, “You know that you’re never number two/Number one’s gonna be number one” and promising “I’ll be good, I wish I could/Get this message over to you now.” He realizes that it might be too late. There’s both a swagger and a vulnerability on this song and this record that adds to its push-pull appeal. It’s a song that was often interpreted as a message to his audience, his bandmates, and his label.

There’s a lot of church on Fresh. In “Let Me Have It All,” the first line is “You have turned into a prayer/I can feel I’m almost there.” If “If You Want Me to Stay” is a swaggering demand that if his lover wants him around, she has to accept him as-is, then “Let Me Have It All” is a desperate prayer, a plea to his lover. He even implies that he’s not fully himself without her, and her mere presence is a balm: “Just to be near you is to be/Let me have the rest of me.” A repeated line is “You set up a barrier/Don’t you know I’d marry ya?”, indicating that he wants it all with her, if only she’d let him. The song features more call-and-response straight from gospel music and blues, as well as the prominent use of the organ. The drum machine and squawking bass add to the dirty feel of the song; so much of this album evokes a late night, into the most desolate of hours. There’s no resolution in this song, only tension, which is reflected by both the lyrics and especially the extended notes played by the horns that don’t resolve into the rest of the music.

“Frisky” is a light-hearted song after the first three intense tracks on the album. It’s heavy on descending notes at first, but the song itself is in a bright key and there are plenty of upswells in the horn parts that reflect the overall optimism of the song. It begins with Sly admitting “I gets all the way down/If I don’t keep smilin’ wit’ y’all.” He says, “That’s why I keep music/All around the bed,” which allows him to call Frisky. It’s unclear if Frisky is the name of a girlfriend or just a state of mind he’s trying to achieve creatively, but it’s yet another strong statement that details Sly’s inner struggles and how he tries to cope.

That comes to a head with the heaviest song on the record, “Thankful ‘N Thoughtful.” This is the feeling you have after making it through a harrowing night, whether it’s being in a dangerous situation, heavily abusing substances, or simply dealing with the isolation of mental illness. It’s an appropriate capper for the album’s first side, one where Sly was doing some heavy thinking about his life and the people who were in it. The tempo is slow and revolves around the drum machine, some funky bass playing, and electric piano. It’s “early Sunday morning,” but Sly “forgot my prayer.” He got away with something, because “Something could have come and taken me away/But the main man felt Sly should be here another day.” All of this makes him pause, making him “Thankful” and “Thoughtful”—those two words are blasted through by Little Sister.

It is a song about gratitude, to be sure, but it’s about the feeling of being granted an extra chance—and maybe not one he deserved. After all, “I’ve taken my chances/I could have been dead.” He knows his lifestyle is not sustainable, but he has a sense that everything will work out. He also advises unnamed others that he could have taken what they have, and they should be grateful as well. He even credits his mother for the idea of making this song, because it will help others. He’s telling everyone to count their blessings. The music is complex rhythmically, but it’s not as layered as “In Time.” The horns blast through with repeated riffs over the chorus, as though they are commenting on it somehow. However, the real highlight of the song is Sly’s vocals, which may be the greatest of his career. He inhabits the spirit of a bluesman on this song, but his tone is so varied and rich that the listener treasures his every utterance. The growls, the screams, and the wails all add to the song’s emotional resonance, but it’s his precise enunciations on some words and his slurred notes for others that make this such an unforgettable listening experience. It is Funk Gospel, recorded without an ounce of irony.

Side two of Fresh begins with a personal statement: “Skin I’m In.” There’s a long, funky bass section that starts the song before the horns and lyrics brightly mix together. “If I had to do it all over again,” Sly declares, “I’d be in the same skin I’m in.” In other words, no regrets, even as he ponders “The things they dare me to do” and the “Things I never win.” He’s not blind to his bad choices nor to the way some people treated him, but it’s all part of the deal. The horns are pushed way up in the mix, and as they are arranged on most of the record, they create a separate, repeating riff instead of doubling up on the main melody.

“I Don’t Know (Satisfaction)” takes the partial structure of a cover, but it’s one of Sly’s few songs that’s clearly directly written to not just his fans, but to Black people in America. It addresses his skyrocketing fame (“Bigger crowd, feelin’ proud/And all of a sudden I’m singin’ loud”) but also acknowledges the ways in which he felt used (“Now I know what to do/No more sellin’ me to you”). He is sympathetic to the violence and frustration of riots, but suggests pragmatically “Much to learn, a place to turn/When there’s nothin’ else to burn.” The song begins with Little Sister repeating the chorus (“All we need is, little action/If it’s only but a fraction”), which is sung with the same cadence as The Rolling Stones’ “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction.” Sly cleverly spins out the multiple meanings of that song and creates a different set of meanings. Sly uses both “I” and “We” in this song, making it both personal and pointed.

“Keep On Dancin'” begins with a reference to one of the most upbeat, group-oriented hits of the band, “Dance to the Music,” and turns it into a downbeat, legato funk track. The slurred, repeated strains of “Dance to the Music” from Little Sister are almost uncomfortable to listen to if you know the original song, making “Keep on Dancin'” feel a beat too slow. That effect is clearly intentional, as Sly wants to disorient the listener as they hear this song about addiction and a woman he’s into, and how her presence helps “them Joneses, let us alone.” This track also clearly shows the difference between Sly’s new working methods and old, as the original song highlighted every band member, both in terms of voice and instrumentation. This track, with the exception of the muted backup singers, is all Sly.

There is a degree to which some elements of the back half of the album are made up of older, unused tracks, or tracks originally meant for another project. This is true of the only cover song released by Sly & the Family Stone, “Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be).” This was originally written years earlier for singer and actress Doris Day, and it wound up becoming her signature song, much to her chagrin. Sly was friendly with Doris through her son, writer and producer Terry Melcher. The original song is fast-paced, saccharine, and has a cheerfully twee orchestral accompaniment. Sly had originally intended for this to be a track for Little Sister, something that never materialized. Instead, he recorded it with his sister Rose singing lead, although Sly sang on the chorus and gave some call-and-response feedback.

The result is surprisingly funky, soulful, and delightful, without a hint of irony. Sly and his sisters take this song to church. There’s a delicate guitar solo, and it also happens to be the last track for the group that Larry Graham played on. His part is so spare, one barely knows it’s him. The pace of the song is almost agonizingly slow, as Sly wrings out every bit of soul in his vocal responses to Rose, and Little Sister’s voices are simply ethereal. The biggest musical mood-setter is the organ, which provides a beautiful counterpoint to Rose’s delicate voice and Sly’s gritty howls.

The final two tracks feel like Sly filling out the album. “If It Were Left Up to Me,” is an unused track from 1970, and it sounds like it. The thumping but simple bassline, the group vocal, the second and third-person (you and we) perspective…it’s perfectly fine, and quite familiar. The lyrics are both urging the listener to make changes in society but also promising the singers will try too. This was probably going to be another track for that unreleased Little Sister album.

The final track, “Babies Makin’ Babies,” is more of a mood piece than a fully-fleshed out song. There is a deep, low, and insistent bass groove that is paired with the high notes of Little Sister, the organ, and Sly’s own falsetto. It’s not so much a lecture on the phenomenon of people having children at too young an age and more of a statement of fact. It’s not quite apathetic and detached in the way that Riot was, but the only thing it urges is to “Tell the truth/to the youth.”

The first side of Fresh is as good as any album ever recorded, in my view, and the second side still has plenty to recommend to it. While it may not receive the same attention as his earlier work for a variety of reasons, it certainly had an impact on critics and musicians alike. Funk, in some ways, was the one missing ingredient from the 60s output of Sly & the Family Stone, but this album proved that Sly was once again miles ahead of his peers. Unfortunately, it wouldn’t last.

Sly’s further descent into drug use (alluded to on this album but with the sense he had a brief reprieve) is well-documented. He still put out a few more albums, but this was the last one that had most of the original members involved in some capacity. He’d continue touring and appearing on television into the early 80s, and he also joined Funkadelic on their final release. After that, Sly avoided recording, public appearances, and recording new music for a long time. He did show up at the last second when Sly & the Family Stone was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and he also penned his own memoir in 2017. It’s not easy being a prodigy, and success is not necessarily the balm for an anxious soul that one might think it is. Sly at least left us with one brilliant, unfettered look at his genius on Fresh, an album that bears studying from musicians from any and all genres.