This post is also available in:

日本語 (Japanese)

This large sign, emblazoned with the words がんばろう!石巻 meaning Let’s Go, Ishinomaki, was found placed in the ruins of downtown Ishinomaki just beyond the seashore shortly after the disaster to rally the community. It was preserved and is now displayed in the Kadonowaki Elementary School’s restored gymnasium.

I am so grateful that at the last minute I was able to arrange a visit with composer Aya Nishina (I’ll have more on that visit with her in another article!) in her hometown of Sendai, the largest city in the north-eastern region of Tohoku. At her suggestion, I took a day to visit Ishinomaki, a city a short train ride to the north of Sendai that had suffered the greatest loss of human life during the March 11, 2011 Great East Japan earthquake, tsunami, and ongoing nuclear disaster but had since, she said, shown remarkable spirit and creativity in rebuilding and moving forward.

3,187 citizens of Ishinomaki died with 415 more still unaccounted for. Approximately 33,000 homes in Ishinomaki were completely or mostly destroyed, 56,708 buildings damaged, leaving 50,000 out of 163,000 residents displaced. Demonstrating great collective spirit and creativity in working together to revitalize their community, the residents of Ishinomaki and the surrounding communities had established a summer arts festival and created their own memorials to those who had been lost and opened an educational center to aid in preparing future generations for the next disasters.

I had long wanted to visit because I felt a personal connection to the area. Shortly after the disaster, I had found and read Letters from the Ground to the Heart — Beauty Amid Destruction, Sendai-based English instructor Anne Thomas’s extraordinary account of the many acts of kindness and miracles she experienced in the days after the disaster:

I come back to my shack to check on it each day, now to send this e-mail since the electricity is on, and I find food and water left in my entranceway. I have no idea from whom, but it is there. Old men in green hats go from door to door checking to see if everyone is OK. People talk to complete strangers asking if they need help. I see no signs of fear. Resignation, yes, but no fear or panic. [p. 13]

Somehow at this time I realize from direct experience that there is indeed an enormous Cosmic evolutionary step that is occurring all over the world right at this moment. And somehow as I experience the events happening now in Japan, I can feel my heart opening very wide. My brother asked me if I felt so small because of all that is happening. I don’t. Rather, I feel as though part of something happening that is much larger than myself. This wave of birthing (worldwide) is hard, and yet magnificent. [p. 14]

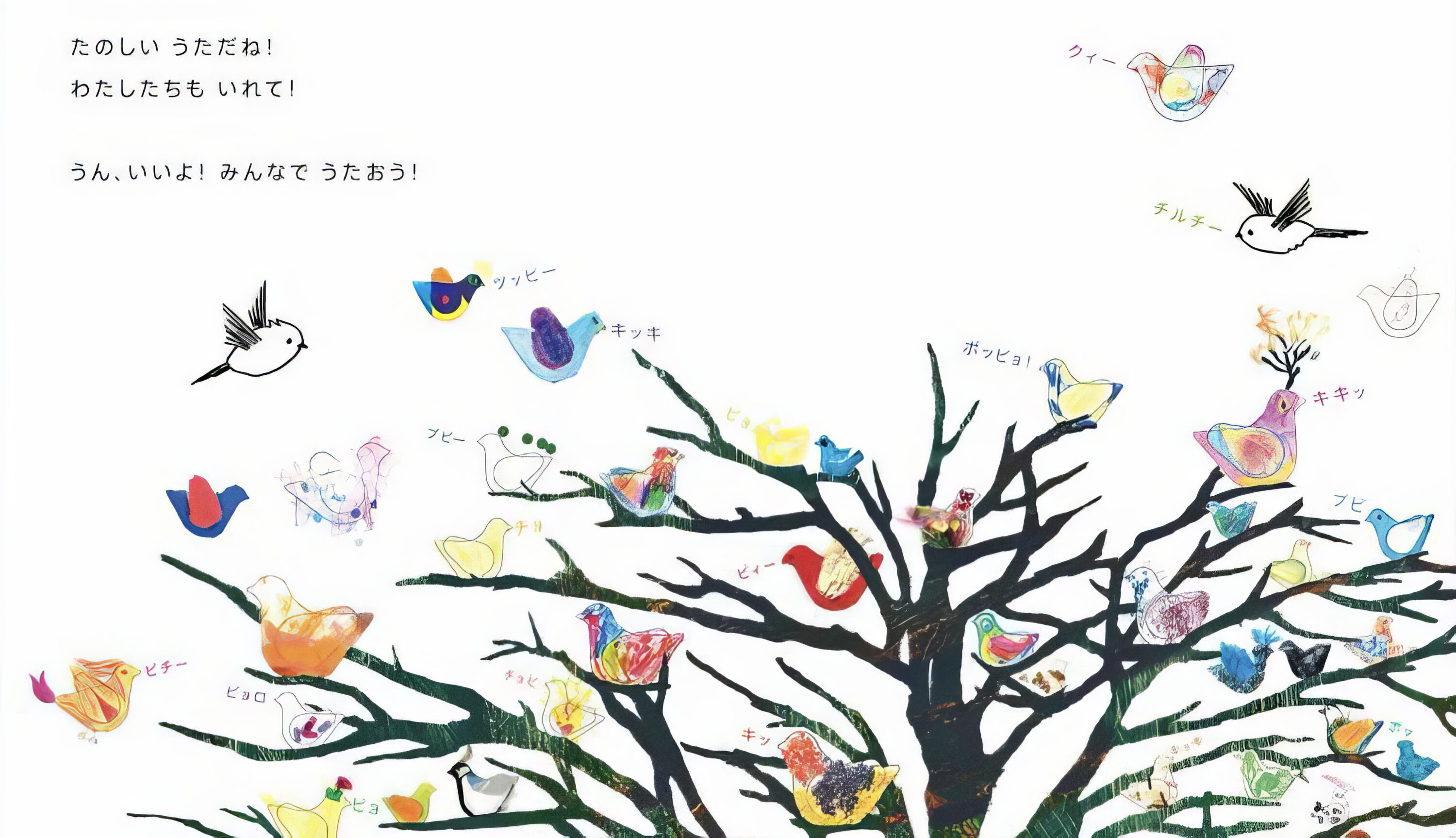

Then in 2012 I led the NYC community’s participation in the 500 Frogs project, which was initiated by Deb and Randy Buckler of Resins by Randy. Because the word for frog in Japanese, kaeru, also means return, they decided to create hundreds — perhaps 1000s eventually — of white resin frogs that people could paint and return and that they would then send to children in the disaster-struck region, many of them still displaced.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham Photo © by Hands on Tokyo

Photo © by Hands on Tokyo

Photo © by Miho Tsujii

Photo © by Miho Tsujii Photo © by Miho Tsujii

Photo © by Miho TsujiiIn 2018 on the 7th anniversary of the disaster, I organized a healing circle and dance/music benefit concert at CRS in celebration of the people of Tohoku. Wishing to support an organization providing arts and healing services directly to a local community within Tohoku, we choose to donate the proceeds to the non-profit community center O-Link House in Ogatsu-Cho. Ogatsu is a more remote community within Ishinomaki-Shi, and its population declined by more than half due to loss of life and displacement. According to Asahi news service, “watermarks showed that the waves rose as high as 21 meters” there and “eighty percent of the houses and other buildings in Ogatsu were destroyed.”

With so much of the infrastructure of Ogatsu destroyed and many of its remaining inhabitants more geographically scattered and cut off from another than before, O-Link House provided critical community art, crafts, healing, cultural programming, and advocacy for those remaining in this most isolated area of Ishinomaki. According to Hands On Tokyo, which helped to fund and construct the facility following the disaster, it included “a café and library, a space for the preservation of industry and traditional culture (fishing and ink-stone handcrafts), and a study and recreation space for all ages of people who live in and around Ogatsu.”

I had connected with them via colleague Miho Tsujii 辻井美穂, an artist “primarily concerned with regenerating life at the foot of destructions” who had traveled to O-Link on multiple occasions to lead some community art projects — and whose performance I would see in Osaka later in the trip. In April and May of 2015, she, together with Chizuru Hatayama of O-Link, organized women in Ogatsu, many of whom are adept sewers, to participate in the “Ohariko (Stitchwork) Project” at O-Link, using the creative skills they practice to express themselves and be communal through sewing.

It was also part of an exhibition about WWII, speaking to the wartime practice wherein mothers and wives would stitch 1000 knots on a belt to give to family members who were being sent to war. Following the war, this practice had been criticized as yet another example of society-wide blind support of militarism. This workshop created an opening to reflect on what those earlier women might have been thinking and feeling during a time when they had no other choice but to stitch protective amulets for soldiers.

Miho also created a giant mandala out of lights at the very spot where the tsunami entered Ogatsu City. She asked people what would symbolize their town, and people said their city logo, which had disappeared after Ogatsu became absorbed as part of Ishinomaki City. Lost in the rubble left behind by the tsunami, Miho found a large stone bearing the words Ogatsu City from the time when it had been an independent community, put it in the center of the mandala, then used light bulbs to create the shape of the city symbol. Dancing around the mandala accompanied by local ryuteki traditional flutist Susumu Yanashita 山下進, Miho created an original performance with a ritual effect in remembrance of those who had been lost. Attendees said afterward that they felt that the souls who had been taken by the waves were dancing there, too, and many people cried — good tears.

Unfortunately, O-Link House stood where the government, as part of its own revitalization plan, insisted upon building a new road, and so the building, which had itself earlier been built with disaster assistance funding a few years before, was razed. The community lost its only art center. The prefectural government, despite the opposition of the local community, also constructed an enormous sea wall, which blocked the view of the ocean except from higher elevations as well as access to it, further damaging the already decimated fishing trade around there. While local residents wanted to rebuild and continue adapting to life within their beautiful but vulnerable natural environment, with greater awareness of the possibility of future large tsunamis and where to build and where to evacuate, their voices and desires were ignored. It seemed that the prefectural and national governments were primarily interested in making it easier for the remaining residents to leave.

Since O-Link House was in a relatively remote location, I was unable to find anyone on this visit who personally knew any of its former leaders, but upon arriving at Ishinomaki Station, I did discover that there was now a Reborn Art Festival cafe called the Reborn Art Stand there, where I was able to learn more about their ongoing work. Based on the concept of “Reborn Art” as a means of living, the Reborn Art Festival is a comprehensive festival of art, music, and food that has now been held three times since 2017 in locations throughout Central Ishinomaki and Oshika Peninsula.

While no new festival has been held in the past two years, the Festival continues to sponsor and promote various art, music, food, and nature happenings in the area, and the Festival’s station cafe, which opened in November 2023, serves as a point of introduction to the festival and area artists. Many festivals with outdoor events feature food vendors, but it seems fair to say that for the organizers of the Reborn Art Festival, the connections between nature, culture, food, and sustainability run deep.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamIshinomaki, adjacent to one of the world’s largest and most important fishing grounds, has more than 200 abundant fish species. Although its fish market was quickly rebuilt after the tsunami to be the largest in Asia and is again booming, many varieties of fish are unused or underused for various reasons. Deer are also considered sacred in this region — there is even a nearby island, Kinkasan with a deer shrine where they are carefully protected — but the population In the surrounding hills and mountains has been growing and more frequently entering the town, resulting in increasing damage. The Festival has sought to address both issues by creating innovative oden (a type of soup typically made with fish cakes and veggies in broth) and taco dishes using the otherwise unused fish and venison as well as local mountain vegetables.

In the same vein, the festivals have featured many site-specific installations and events embedded across the natural landscape of the area in ways designed to heighten awareness of the interdependence between humans and nature. For example, for the 2021 Festival, artist Kohei Nawa created Oshika (White Deer), a soaring white deer statue and installed it on the beach of Ogihama on the Oshika Peninsula, the area of mainland Japan closest to the epicenter of the 2011 earthquake. The deer seems to change colors with the shifting tides and the rise and fall of the sun and evokes both the lost deer that wander into human settlements as well as the sacred deer living across the bay on Kinkasan. The location itself offers an excellent view of the beach, the sea, and the newly rebuilt urban areas, and the path leading there, covered by thousands of white stones which accumulated naturally over the millennia, features a seasonally-changing sound installation and a nearby man-made cave used to host periodic Festival happenings.

In conjunction with the Festival, Nawa also invited French Belgian choreographer and dancer Damien Jalet, several dancers, and the pianist Koki Nakano to spend time in Ishinomaki in 2019 exploring, in Jalet’s words, “different points of fusion between the human body and the landscape, especially in the areas where the wave hit. They mainly focused…on feeling, catching and rendering the healing and repairing forces that pass through everything that is alive.”

Dancers : Aimilios Arapoglou , Mayumu Minakawa, Jun Morii, Ruri Mitoh, Benjamin Bertrand, Wataru Murakami

Pictures by Yoshikazu Inou

Many of the residents of Ishinomaki, painfully aware of their region’s particular susceptibility and vulnerability to natural disasters, have found their own ways to demonstrate their appreciation for their interdependence with nature. One woman with a passion for Chinese medicinal foods opened bi cafe Natsume in a serene, 2nd floor, light-filled space overlooking the Kitakami River in the center of Ishinomaki City on June 20, 2020. There, she serves a variety of medicinal teas and delicious hotpot and curry dishes infused with healthy Chinese herbs. The day that I visited, a group of women came in to enjoy the lunch sets. While the cafe welcomes everyone, it seems to be a place where women can and do often come comfortably by themselves to refresh body and mind.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamIn nearby Momoura on the Oshika Peninsula, some local participants in the Reborn Art Festival have created Momonoura Village, an accommodation and training facility where visitors can learn and enjoy “how to live” with nature. The area has very little flat land between the mountains and sea, and in the aftermath of the tsunami, much of that has been ruled unsafe for rebuilding. To support the remaining residents and fishing industry, this small eco facility was built on terraced land that was previously used for farming to educate visitors about eco living and the local fishing customs. Guests can experience fishing and oyster harvesting and food preparation while staying in simple guest facilities built using materials found on site.

Much of what I learned about Ishinomaki’s experience with the disaster I owe to an Englishman, Richard Halberstadt, who was the only English speaker I met in Ishinomaki. He is responsible for virtually all of the English-language materials about the disaster that one can find at the local tsunami memorial and museum, as well as anywhere else in town as far as I could determine.

Like Anne Thomas, Halberstadt was also an English professor in Miyagi prefecture — in his case at Senshu University in Ishinomaki — when the tsunami struck. It was spring break that week but he had decided to go into the university that day anyway, which likely saved his life as his home was flooded while the university, located further inland on higher ground, was spared. Although the British government advised all of its citizens to leave Japan following the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Halberstadt defied the order and stayed to help the community that had treated him as one of its own.

In 2015 the city hired Halberstadt to run the Ishinomaki Community & Info Center (ICIC), a small, temporary place created that year to display information about the damage the disaster had caused and the plans for rebuilding. and provide an English-speaking point of contact for foreign visitors. Halberstadt had made many friends in the community while working some years earlier as an actor on a project re-enacting the departure of the San Juan Bautista, the first ship to carry a Japanese to Europe, from Ishinomaki harbor in 1613, and it was agreed that Halberstadt’s friendly nature and comfort with public speaking would make him an ideal person for the job. His ability to speak English was considered a plus should any foreigners visit —and to their surprise a great many did!

“Having been spared while friends of mine perished, I began to feel that I had a duty to live life on their behalf as well. When the ICIC opened, I had a feeling that this was my purpose. I can spread the word about what a great community Ishinomaki is, and being bilingual helps me reach a wider audience. People come here from all over the world to see what it’s like in the stricken area and to learn from the disaster. When someone tells me how helpful it was to hear a coherent explanation in English, I feel that what I’m doing is really worthwhile.”

Later, when the city opened a memorial museum at the site of the ruined Kadonowaki Elementary School, the ICIC was closed and Halberstradt was hired to run the new permanent memorial center. It was there that I met him. Even though many foreigners had visited the ICIC, apparently little thought had been given to making the new memorial welcoming or accessible to them, but Halberstradt has managed to translate a lot of the materials into English. The devastation that the school suffered has been preserved so I could see it first-hand, but the English-language explanations that Halberstradt provided really helped to bring the story of what happened to life for me in much greater detail, and I am grateful for it.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamHalberstradt could have given in to the impulse to see himself as an outsider, an Englishman, and left. Instead, he strayed, trusting his heart, which told him that this community had become his own. Because of that trust and that love, Ishinomaki’s many miracles in the face of tragedy have become accessible to visitors from all over the world.

Seeing the ruins of the school, the children’s overturned and charred desks, their drawings still readable on classroom chalk boards, and reading about their experiences minute by minute was quite overwhelming. I thought again of Anne Thomas’s words: “I see no signs of fear … I can feel my heart opening very wide.”

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamThe story of the Ishinomaki’s experience with the tsunami has been told at length in English elsewhere, so what I would like to share here is how impressed I was by the cooperation of the school children and by the quick-thinking, selflessness, and courage of the school’s teachers and staff, who succeeded in evacuating and saving every child present up the mountain side behind the school.

I had known that some schools had been destroyed, and I had known that there had been fires, but I hadn’t really grasped that the tsunami itself swept large amounts of burning debris — cars, boats, entire buildings — inland, spreading the fires, until I saw the ruins up close and in person. The tsunami waters reached high up the 2nd floor of the three-story concrete school, and its fires burned out even the third-floor classrooms, so if the school staff had elected to have everyone ride out the tsunami on the top floor or on the roof, out of reach of its waters, they would have all perished in the flames. In fact, some 500 residents of the school’s surrounding neighborhood did fail to escape the reach of the tsunami and the fires and were lost that day.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamThe teachers and staff instead led the children out of the school and up the slope of Mt. Hiyori behind it just as their emergency manual instructed and as they had regularly practiced in evacuation drills. Some townspeople unfortunately evacuated to the school shortly afterward, even though the school had not been labeled as an official evacuation point, but even they were saved by the quick-thinking school staff who had decided to risk their lives to take care of anyone else who might show up. Although the rising waters quickly trapped them inside the school, the staff managed to create a makeshift structure using classroom furniture across which they could crawl from a higher floor of the school to the mountain side, and they left no one behind.

Of the many stories that the museum conveys, I was perhaps most moved by the testimony of one teacher who was herself a mother whose children attended a different school. Once she had evacuated her own students, she managed to find her own children but then informed them that she must return to the evacuation site to be with her students who had not yet been picked up from the evacuation site; some would not be picked up since their parents had been killed and no one had any way to know if they were lost or merely cut off and delayed, and it was extremely cold and there was no power and little food and the children were alone in the midst of this. The teacher’s own children begged her to remain with them. She felt it was her duty as a teacher to look after her students first, but she felt tremendous guilt afterwards even though her own kids were safe where she left them.

The successful evacuation was only possible because of careful planning, preparation, and execution of the plan. That this should not be taken for granted is a critical lesson that the museum’s curators convey. “Only by constantly learning from experience and reminding people to keep the lessons in mind and remain vigilant, can we reduce casualties in future disasters,” Halberstadt said.

This is made abundantly clear by the contrasting fate of Okawa Elementary School, located in a more rural area of Ishinomaki. There, the school leaders had failed to prepare a specific tsunami evacuation plan, believing that no tsunami would ever reach their area, as it was 4km inland. Following the earthquake, the staff brought everyone outside to the school yard and dithered and argued about what to do, rebuking the pleadings of the children to climb the hill right behind the school (which you can clearly see in the photo of the school ruins below taken by Ian Monroe on March 12, 2012 and used here under CCL 2.0). After receiving reports that a large tsunami was coming, they tragically decided to lead everyone to the entrance of the nearby New Kitakami Great Bridge, which spanned the Kitakami River, thinking that location would be high enough. But the tsunami, when it came, was much higher than they had imagined, having been funneled by the riverbank, and it came not as a single wave but as the entire ocean rushing toward them. 10 out of 11 teachers and staff and every child present but four, who had disobeyed the adults and run toward the hill, were lost, 74 out of 78 present, nearly an entire elementary school of children lost (30 had already gone home or did not attend that day).

And even those few children who disobeyed their teachers and fled were still caught up in the tsunami’s waters but were high enough or simply fortunate enough that they were carried along the top of the water. One of the boys, 5th grader Tetsuya Tadano, became trapped between a tree and the rocks and thought he would drown but the waters brought him together with another boy, classmate Kohei Takahashi, who suddenly reappeared beneath him having floated for awhile in a household refrigerator that had come to him. They were able to save one another, although not without sustaining serious injuries. The water had moved so fast and forcefully that the rim of the hard hat that one was wearing was driven into his eyes, leaving him with impaired vision for quite some time and both sustained various other injuries. But because those two survived, we have an account of all that went wrong there. Years later, despite the government’s seeming unwillingness to establish responsibility for the catastrophic loss of life, a court determined that the school was liable and awarded the grieving parents financial damages.

Photo © by Ian Monroe

Photo © by Ian MonroeOne teacher at another school, Hiratsuka Shinichiro, who lost his then 12-year-old daughter Koharu in the Okawa tragedy and is now a principal at a nearby junior high school, spent years trying to make sense of the Okawa staff’s refusal to evacuate up the nearby hill so that schools could be better prepared for the next disaster. He now brings teachers to the ruins of Okawa Elementary School and teaches them to guard against normalcy bias, the tendency to downplay or disbelieve dangers to avoid or cope with fear, majority synching bias, the tendency to follow the group even when you think it may be making the wrong decision, and psychological detention, the tendency to stick to a decision even after its wisdom and has come into doubt.

The Okawa school staff, as well as many other community members, must have been skeptical that the tsunami warnings applied to their area because the last large tsunami to strike the area had occurred in 1933, meaning few local residents had experienced one first-hand, and no tsunami in modern history had ever reached this particular area. Indeed, the Okawa Elementary School was itself labelled an evacuation point on community emergency map.

Furthermore, the school staff apparently saw and heard of other people calmly going down to the river and toward the sea to watch for the tsunami, imagining it would be something to see but not be threatened by, and may have been wrongly reassured. Shinichiro and others like him now do their best to ensure that sound disaster response plans do, in fact, plan for the unexpected and that regular drills are held to instill the habit of following the plans, even when the mind is tempted to avoid acknowledging or facing potential dangers.

In the early years of the post-disaster recovery, many traumatized community members wanted to erase all traces of the disaster as quickly as possible, a sentiment that I later learned was also prevalent in Hiroshima following its bombing. Even the Ishinomaki Community and Information Center had been forced to operate without a sign out front lest it trigger still traumatized survivors walking past. But just as in Hiroshima, the efforts of a few determined citizens who insisted it was better to face what had happened and learn from it rather than forget it led to the preservation of some of these disaster ruins.

The lesson that I received from this is that these citizens, by trusting the human spirit’s capacity to survive even the most horrific tragedies, have instilled in their neighbors the courage and determination to face and prepare for future disasters. Because of this, numerous efforts to memorialize the lost, uplift the survivors, and educate future generations now enliven and unite Ishinomaki, inspiring its vibrant recovery and transforming it into a source of inspiration and learning for visitors from all over Japan and the world. And this did not, does not, happen by accident. It is the demonstration of the conscious choice and application of love over fear.