This post is also available in:

日本語 (Japanese)

Since the founding of Shihonryuji Temple (which later became Nikkosan Rinnoji Temple) by the Buddhist monk Shodo in 766, Nikko, a small town about 90 miles north of Tokyo in Tochigi Prefecture, became known as a sacred place where Buddhism was brought into harmony with the older Shinto worship of the mountain gods. Eight centuries later, Shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu’s mausoleum was constructed in Nikko, 208 steep stone steps up the mountainside above the other temple buildings. So great were his accomplishments — the dynasty he founded ruled Japan peacefully for 250 years and oversaw its greatest cultural flowering, known as the Edo Period — that succeeding generations could not resist making his shrine, as well as the adjacent temple and shrine complexes, more and more grand, and there are now 14 centuries of philosophical and artistic contributions to explore and unpack.

Nikko was the only place I visited during my month in Japan where I did not talk with anyone. I learned some history and enjoyed the architecture, art, and natural environs of the temples and shrines, but I will admit up front that I struggled to go deeper. Nevertheless, I hope that what I did experience there might be of interest.

I could not understand to what extent Shodo and his intellectual/spiritual descendants succeeded in synthesizing Shinto animism, Zen, and Confucianism. The messaging here feels confusing and even oppressive at times, particularly as the mass influx of casual tourism is so heavily courted and the melange of messages and imagery is by and large presented without explanation. Later in my trip, I went hiking with a woman from England who told me that she felt Japan is littered with too many signs, yet too few containing the information ones really needs where one needs it.

How do the Confucian admonitions to avoid evil and live a life of moderation really fit with the presence of an extravagant gold-leaf-covered temple or the concepts of animism, or the traditions of Zen Buddhism practiced here, to say nothing of whatever it is that Tokugawa Ieyasu stood for? I am none the wiser. The original intentions and historical contexts of the many cultural treasures here, while not erased, are all too easily flattened into a series of Instagrammable moments. What I could feel is that I spent time with some masterfully crafted artworks and structures that are old and have been extremely well taken care of for a very long time, and that there seems to be a longstanding and overriding desire to accept (collect?) and harmonize.

Climbing those 208 steps was a workout. I couldn’t imagine the effort that would have been required to carry the stones up the mountainside to construct his mausoleum. And it was built three times, no less, each time more impressively than before! Within a century, numerous visitors began coming to the shrine to pray to the divine spirit of Tokugawa, referred to by then as Toshogu-daigongen, for favor, and according to some accounts he was considered to be on par with the three Buddhas.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamNikko grew to house more temples than any city in Japan outside of Kyoto. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Shrines and Temples of Nikko lie within the natural splendor of the much larger Nikko National Park. The Site’s two Shinto shrines, the Tôshôgû and the Futarasan-jinja, and the Rinne-ji Buddhist temple collectively encompass 103 buildings, nine of them designated as National Treasures of Japan and the other 94 as Important Cultural Properties.

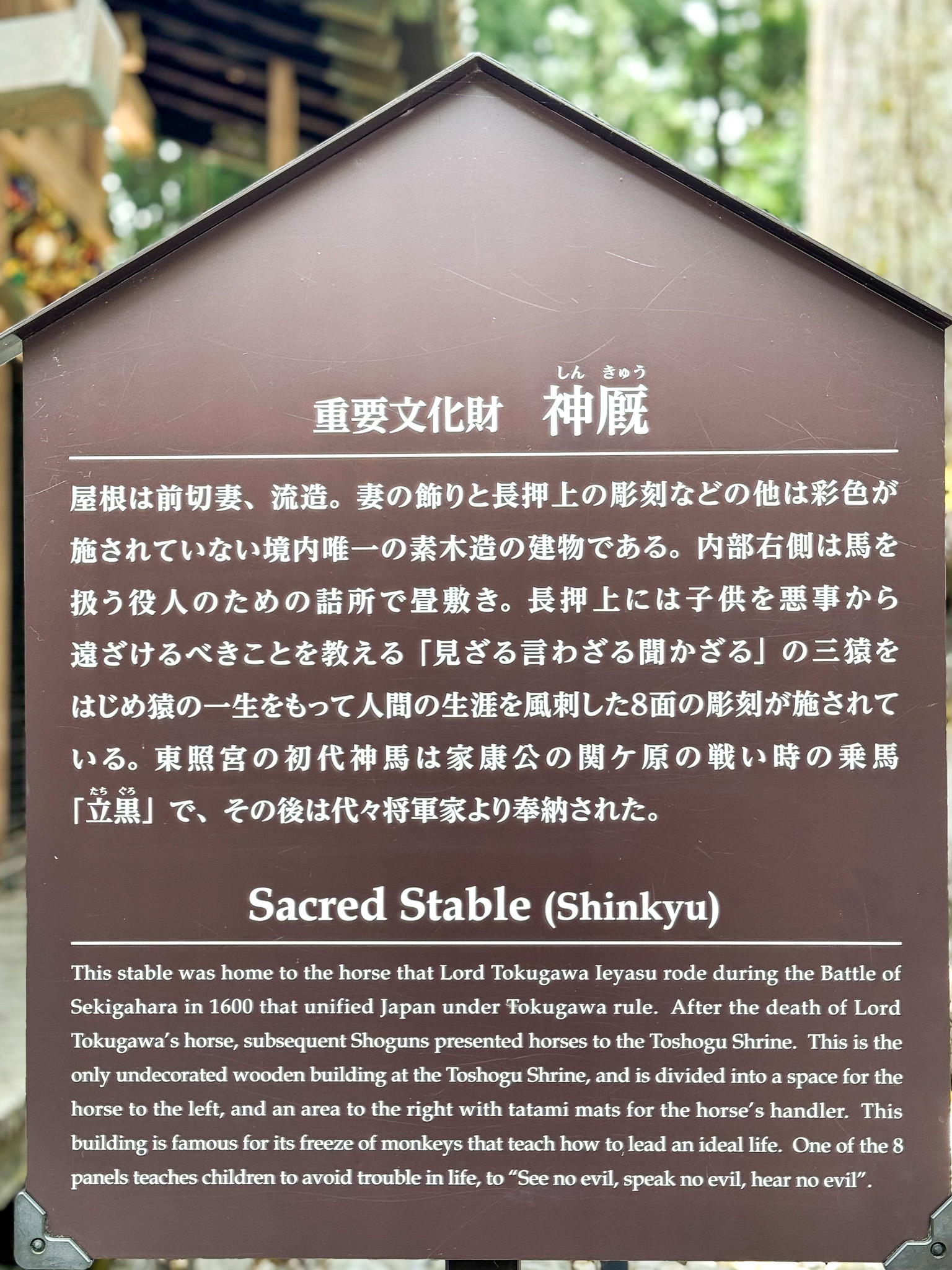

Among the most famous sites is the Tôshôgû Temple’s Sacred Stable, which, though unpainted, features 17th-century carvings of the famous three wise monkeys (“Hear No Evil, See No Evil, Speak No Evil”). Whereas in the West the three monkeys indicate the ignoring of evil, the message here is meant to deter viewers from engaging in evil and is thought to derive from a Confucian teaching imported from China. In addition to housing the temple’s horses, it honors the horse that Tokugawa Ieyasu rode into the famous battle of Sekigahara. What, if any, is the relationship between the monkey carvings and Ieyasu’s horse?

“The stable of the sacred horse at Nikko is decorated with monkeys. It is believed that on New Year’s eve these monkeys come to life and, dressed up in Shinto-priest’s garments, pay honour to their companion … Formerly monkeys were kept in the imperial stables to (it is wrongly said) keep the horses from sleeping. Artists originally inspired by the monkeys of Nikko have often depicted them in human dress, but the monkeys of the sarumawashi too are always dressed up monkeys.” — The Animal in Far Eastern Art: And Especially in the Art of the Japanese Netsuke, by T. Volke, 1975

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamThe Yomeimon Gate, or Gate of the Setting Sun, stands at the entrance to the Tôshôgû shrine. Said to be the most beautiful gate in all of Japan, it is covered in 240,000 pieces of gold leaf and adorned with 508 carvings of children, saints and mystical creatures meant to instruct and inspire. There is so much detail to take in and marvel at here. It is also sometimes referred to as the All-Day Gate, because one could gaze at it all day without exhausting its wonders. I particularly liked the carved panel depicting the child Sima Guang, a story that dates back to 11th century China. It shows him breaking a pot into which a friend had fallen to free him, demonstrating that human life is more precious than possessions.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamTo visit in the morning before busloads of tourists arrived — they started arriving early, too, unfortunately — , I spent the previous night at the historic Kanaya Hotel, which lies virtually across the street from the Park. The oldest classic resort hotel in Japan, and one of the first to welcome foreign guests, the hotel was founded in 1873 by Zenichiro Kanaya, a musician in the Gagaku orchestra of the Tôshôgû Shrine. Musicians so often serve as points of contact for cultural exchange and drive economic growth. Music opens so many doors.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamSoon after, Isabella Bird, an English explorer, visited and proceeded to write enthusiastically about the hotel and the nearby temples and nature sites in a guidebook she published, and Nikko quickly grew into a popular destination for foreigners. The hotel later welcomed the likes of Helen Keller, President Ulysses S. Grant, and Albert Einstein! Today, the hotel still boasts a lodge-style grandeur and an excellent French restaurant.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamOutside the entrance to the Park lies another eye-catching historic site, the bright red, wooden Shinkyō Bridge 神橋, which crosses the lively Daiya River and is considered one of Japan’s three loveliest bridges. According to the literature, the monk Shodo, whom I earlier mentioned founded the Nikkosan Rinnoji Temple, could not find a place to cross the Daiya River and prayed to the mountain deities for assistance. Two snakes appeared and transformed into a bridge, and the Shinkyo Bridge is said to mark that spot. The bridge is maintained by Nikko Futarasan-jinja Shrine and attained World Heritage site status in 1999.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamOne can read at length elsewhere about all of the temples, museums and artworks inside the Park, many of which are quite stunning. I’ll share that what I found most interesting was that this great center of Buddhist learning, arguably as important in some ways as some of the head temples in Kyoto, was kneecapped by the Meiji Restoration government, which, after 1200 years of monastic efforts to harmonize Shinto and Buddhism, chose to sever Shinto from Buddhism in order to refocus national religious practice to inculcate obedience to the Emperor —and to those behind the throne. In the process, the Meiji political leadership also, in my view, devalued and distorted the animistic essence of Shintoism but that is outside the scope of this article. Anyway, from this point onward, Nikko clearly lost influence. Although the temples are still working temples, they have been relegated to serving primarily as a museum, park, and tourist attraction.

For those who have room to explore the surrounding area – I, unfortunately, did not this time — one can also visit the 100-meter-tall Kegon Waterfall 華厳の滝, said to be one of the three most beautiful in Japan, as well as the also impressive Kirifuri Waterfall 霧降の滝 and Ryuzu Waterfall 竜頭ノ滝, the idyllic Lake Chuzenji, and the many onsen resorts and attractions along the Kinugawa River. Despite my difficulty in engaging deeply with the sites and people here, there is nevertheless much to explore and appreciate and keep one coming back.