This post is also available in:

日本語 (Japanese)

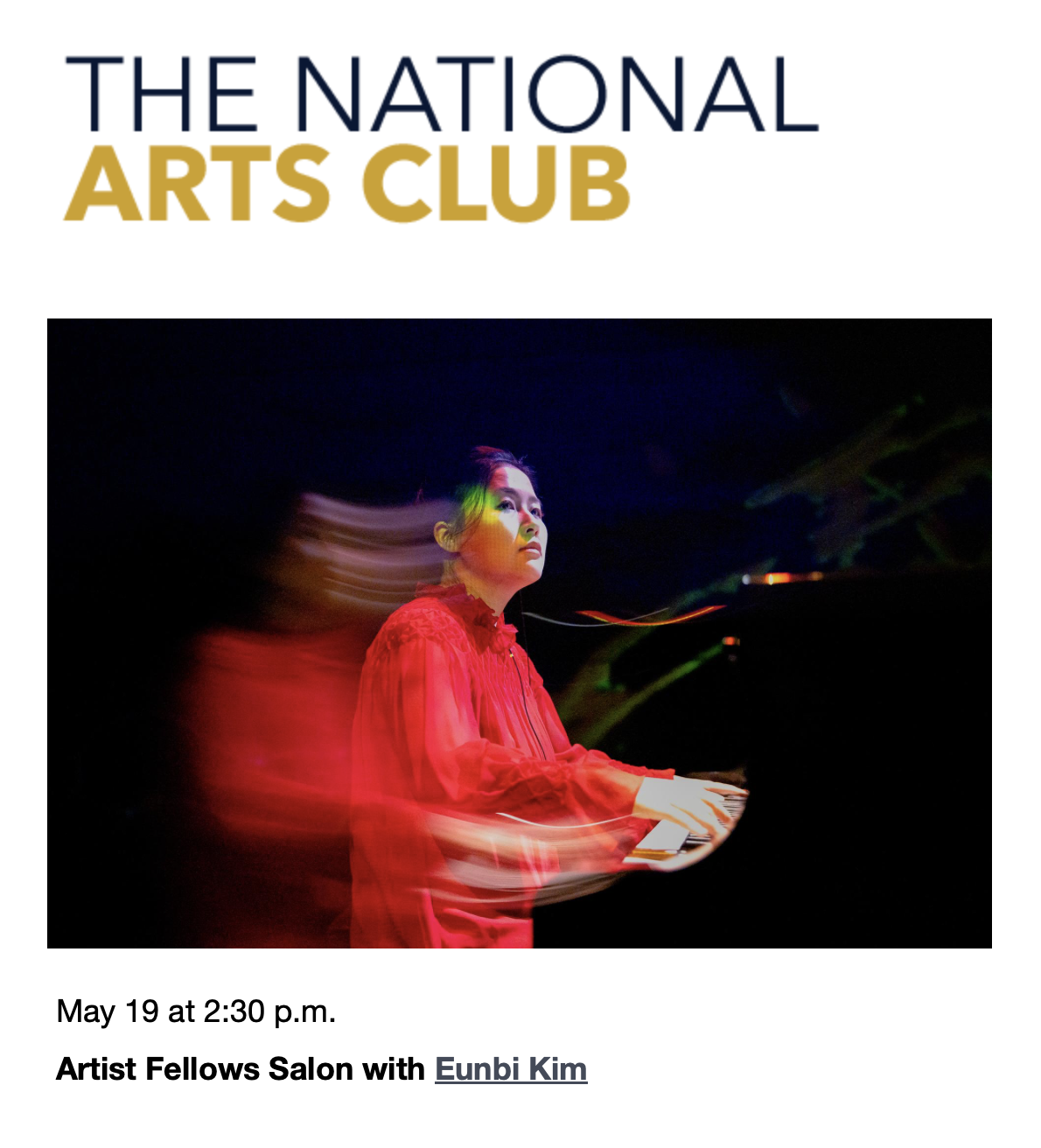

This spring I had the pleasure of attending two uplifting events led by pianist Eunbi Kim at the National Arts Club, where she is one of 14 2023/2024 National Arts Club Artist Fellows. Rather than presenting formal concerts, Eunbi (she/her) created a series of gatherings. This approach suited the Club’s intimate spaces and allowed her to work interactively with the audience, sharing how music and mindfulness practice can work together to connect and heal us. The two gatherings I attended, “How to Love” on March 6 and “Deep Listening” on May 19, each incorporated live music, talking, and visual elements. Eunbi cast the audience as improvisational partners, enabling them to explore the nexus of music and meditation along with her.

For those who have yet to visit the National Arts Club in the historic Samuel Tilden Mansion, a National Historic Landmark re-designed in the 1860s by famed architect Calvert Vaux, one of the designers of Central Park, this former residence features gallery and event spaces open to the public. It is adorned throughout by ornate woodwork, sculptural elements, and stained glass and also houses a restaurant and bar — with stained glass dome! — for members. The Club provides Fellows with several opportunities throughout their residencies to present their work in these lovely and intimate spaces and to meet as a group, share ideas, and experiment together.

Additional perks of the fellowships include membership in the club and keys to exclusive Gramercy Park, providing further opportunities to mix with other member artists of all genres and use the facilities. This year’s Fellows took advantage of the serene and sheltered environs of the Park to explore meditation techniques, sparking Eunbi’s idea to incorporate some of them in her salons.

Photo © by MusikAnimal, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Photo © by MusikAnimal, CC BY-SA 4.0 , via Wikimedia CommonsBefore describing the NAC gatherings themselves, some background is helpful for understanding how these ideas are reflected in the repertory she performed at those gatherings and how all of this fits into her path as an artist.

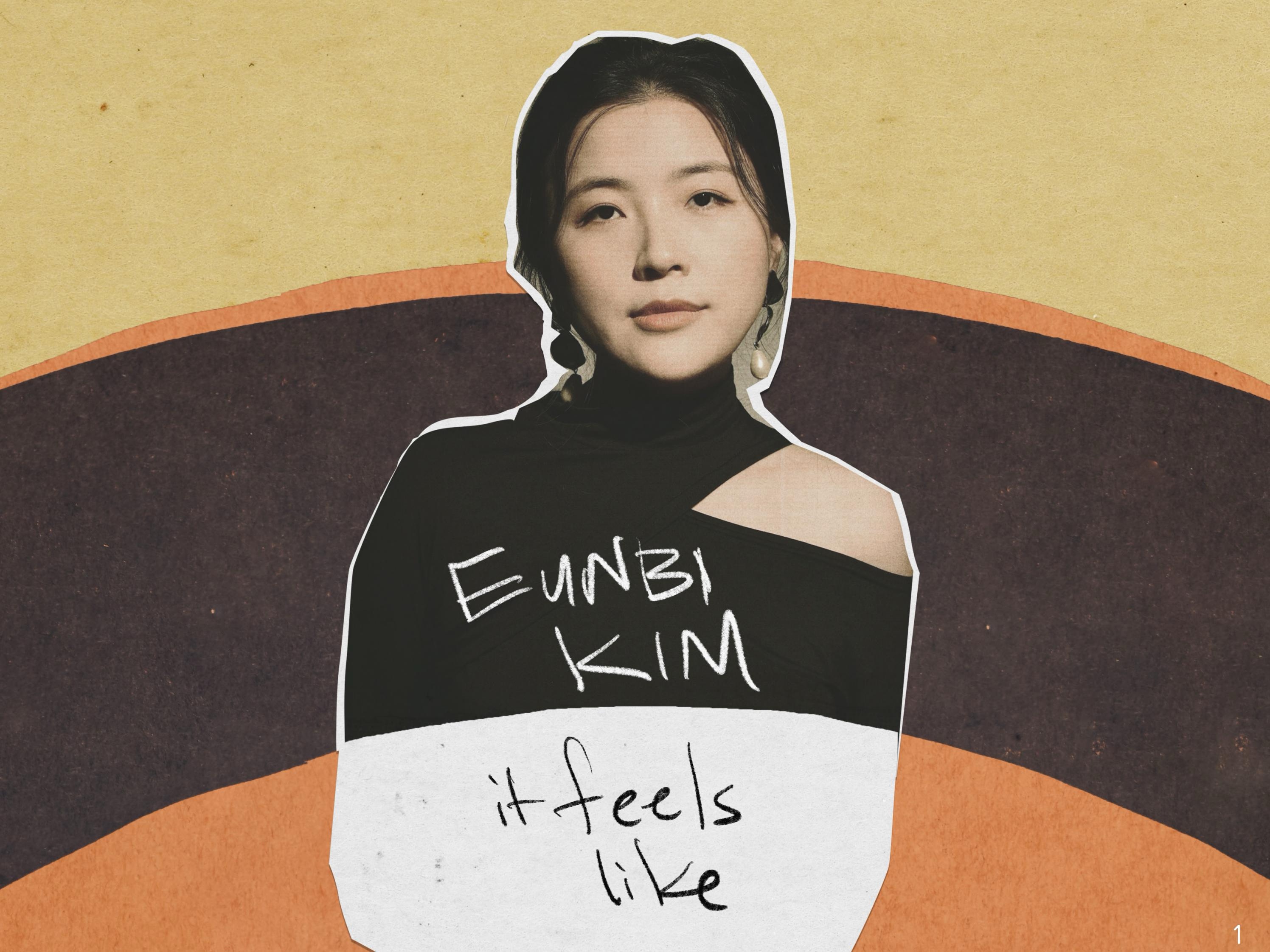

While an accomplished concert pianist, Eunbi (‘eu’ sounds like the oo in “book” and “look”) is known for creating, in her own words, “intimate experiences that transcend the conventions of the piano recital.” Her previous projects have included a concert-meditation performance at Lincoln Center and a TEDx Talk titled “Performing Through Fear.” As an Artist-in-Residence at WNYC/WQXR’s The Greene Space, she created a four-night series, “Eunbi Kim in Residence: It Feels Like,” which mixed live music performances, delicious food, and deep conversations, inviting audiences “to meditate on the parts of themselves that are deeply buried.”

Eunbi frequently collaborates with genre-fluid composers and artists working in other mediums, perhaps most notably creating the music-theater work “Murakami Music: Stories of Loss and Nostalgia,” which she says was “inspired by the music and pianist characters featured in works by contemporary Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami” and featured acting, dance, song, and piano. Numerous presenters, locally, nationally, and internationally, have invited Eunbi to lecture on Murkami’s use of music and to present this show, bringing her to audiences both inside and outside the traditional classical music settings.

This expansive approach has helped her reach new audiences. In 2015, Ian Temple of Superfly.com lauded her for “making classical piano relevant through unique collaborations and interesting subject matter.” Her most recent album, “It Feels Like,” released by the Bright Shiny Things label in 2022, debuted at #2 on the Billboard Classical Charts.

In developing the material for the album, Eunbi said (on the wonderful Crushing Classical podcast, 12/8/22) she wanted to explore “music that can express feelings that are hard to name and memories and feelings that are buried really deep within that can come out and that can be conjured through music or through ideas.“ To that end, she commissioned works by composers Angélica Negrón, Pauchi Sasaki, and Sophia Jani to build around “It Feels Like a Mountain, Chasing Me,” which was composed for her in 2014 by the Haitian-American composer Daniel Bernard Roumain (DBR). Daniel is renowned for the stunning diversity of his sounds and collaborators — from the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company to Lady Gaga to Philip Glass — and his commitment to inquiry and exploration of social concerns. Angelica, Pauchi, and Sophia are also known for their far-ranging collaborations and for combining classical, non-classical, and non-musical elements and reaching diverse audiences. The result is a musically expansive yet intensely personal album. Each track reflects on her life up to that point as a Korean-American born to Korean immigrant parents.

Since Eunbi commissioned these pieces rather than composing them herself, I asked her how they ended up being so autobiographical. She said, “With Daniel, it was totally a surprise.” After approaching him to compose for her in 2014, they hit on the idea of recording ambient sounds from her home window at night to include in the work. However, once he arrived at her home, they realized that it was too quiet, and he instead recorded an interview with her there, speaking about some of her most private memories of her family life. He also recorded a seven-minute phone call between Eunbi and her mother in Korean. She didn’t know what he might do with the recording, but it became a fundamental part of the composition.

Bucking classical tradition, Daniel began the piece with a sample of her talking, sans music, about being afraid of being away from her loved ones. The volume is low, forcing one to lean in to hear it, especially once her piano comes in at a higher level. The spare, repeating piano phrases echo the sadness of the memories Eunbi shares. In places, multiple tracks of her speaking are layered on top of one another, fading in and out, and the piano also comes and goes, in places growing more dramatic as the snippets of speech evoke happier past experiences. The phone conversation in Korean between Eunbi and her mother appears with no music overlapping it, emphasizing her Korean roots and the centrality of family in her life. The 17-minute piece concludes with more ecstatic music and Eunbi musing about death and the future.

Despite referencing some sad memories, Eunbi says she had a happy childhood and a close, loving family life, but it was nonetheless complicated. She hopes this piece’s layered textures and voices express that complication, the totality of the experience, in a way that is hard to communicate through words only. In the album’s liner notes, Daniel writes,

“At times, it may feel like we are eavesdropping on a conversation told between them, in snippets of time and memory. The music and recorded voices work in tandem to create a soundscape and personal experience for every listener to reflect on their own memories, families, and struggles for identity.”

Later, when Eunbi began working on the rest of the album, she says she might have shared that piece with the other composers she commissioned to give them a musical and thematic point of departure. “I think Angelica wrote sort of a response to it. But based on a different conversation, a different topic that was sort of related. And then the other composers were also inspired by conversations we had. And I guess through that they were all related. And Angelica had the idea to use this old Spanish language tape. Pauchy convinced me to record my mother singing. That was a surprise. So, it really was collaborative.”

Sophia Jani, composer of the second track on the album, “Saturn Years,” writes in the liner notes that the title “refers to the astrological phenomenon of the planet Saturn returning to “the same ecliptic longitude it occupied at the time of a person’s birth, which happens at about 29.5 years and which is supposed to shake up one’s life…. In your late 20s, things either start to fall into place or you have to face the fact that parts of your life were built on lies, which you have to accept and correct. This cathartic moment after a long struggle and the final acceptance of having to start over is captured by ‘Saturn Years.’”

This proved to be remarkably prescient. While working on the album, Eunbi got pregnant. Two months after its release, she gave birth to her first child. This led her to reflect on what it means to be a daughter and a mother, on what her own experiences as a daughter meant to her, on how she relates to the world at large, and on what kind of environment and direction she wants to provide her daughter — and herself — going forward. She told me,

“I’m naturally very nervous and anxious, and I endured years of feeling like I needed to always have a perfect performance. I grew up equating myself with how well I played. And I think it’s probably a lifelong lesson for me to learn to undo that completely. And I think I have. And sometimes it comes back. And I’m very critical of myself, too. So it’s always a big struggle for me. And I think meditation helps because if you meditate, if you’re truly present and mindful and you’re really expanding your consciousness, then the anxiety slowly dissipates. I hope my daughter doesn’t grow up being self-critical. I hope that I can support her in environments where she feels free to express herself the way she wants.”

These questions led her to Vietnamese Zen Master Thích Nhất Hạnh’s book How to Love, a concise and easy-to-read guidebook for practicing mindfulness and loving. When it came time to prepare for her spring gathering at the National Arts Club, Eunbi chose to title the program “How to Love,” centering it around two short readings — “Love Is Organic” and “Love Is an Offering” and a hugging meditation from the book:

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham“Breathing in, I know my dear one is in my arms, alive. Breathing out, she is so precious to me.” If you breathe deeply like that, holding the person you love, the energy of your care and appreciation will penetrate into that person and she will be nourished and bloom like a flower” (Thich Nhat Hanh, How to Love (Mindfulness Essentials Book 3), p. 25, Parallax Press).

By sharing some of the book’s themes and exercises in her gathering, Eunbi invited the audience to reflect on these questions and themes for themselves and also provided them with a philosophical and spiritual context in which to experience the musical selections she performed, which included three works from her album “It Feels Like” and two others that, in their way, fit right in with both the album material and the program theme.

The book’s meditation exercises and deep listening techniques build greater awareness of how to bring love into different types of relationships: with oneself, one’s family, and one’s community. One of the central ideas is that these are all interrelated. By coming to understand oneself and the causes of one’s suffering, one develops compassion for oneself and transitions from seeking happiness outside oneself to sharing the love that is, in truth, always present within. At the same time, this practice enables one to better understand and accept others and to heal their suffering when it arises.

The first piece that Eunbi performed in the program, “Marigold,” a world premiere, was composed by Stephanie Ann Boyd, an artist who has devoted her life to creating innovative musical experiences that connect audiences to nature and one another. In fact, she has developed a whole series of works like this one that invite listeners to connect with flora and fauna. The inspiration for this composition was a Polaroid photo of Eunbi’s parents in a field of marigolds. Stephanie found specific musical ways of responding to the photo and the feelings it evoked in her:

“I’ve envisioned this field of marigolds during different times of the day; imagined that space illuminated by different qualities and shades of light. I’ve kept the hands quite close on the piano; sometimes even overlapping each other, to pay tribute to the relationship between Eunbi’s parents. The final melodic fragment of Marigold is a pair of notes, also signifying the love that existed that day between two people in a bright orange field filled with life.”

Daniel Bernard Roumain’s “songs for the alone: II. UnLove,” (2020) and “It Feels Like a Mountain, Chasing Me” (2014) were the second and fifth works on the program. Although “songs for the alone” was inspired by the death of Prince, I couldn’t help feeling that its exploration of grief also spoke to Eunbi’s conversation with her mother in “It Feels Like a Mountain, Chasing Me” where Eunbi says that she wishes she would die before losing her parents, to avoid feeling their loss, and her mother replies no, you shouldn’t think like that because losing a child is the worst thing for a parent.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamIn the liner notes, Daniel writes, “These intimate works explore the moods and modes and feelings of isolation, personal inquiry, and the questioning of ourselves. Each movement expresses grief and depression in their own way. And like any trial or test, there are fleeting moments of light and rare glimpses of understanding, acceptance and love.” Sometimes, we grieve over the loss of a celebrity whom we have never even met personally, and sometimes we grieve for losses that we imagine lie ahead. Feeling connected and feeling or fearing separation can be so bound together.

Jazz master Fred Hersch is represented in the program by “Prelude No. 1,” a spare, melancholy, two-minute track from Eunbi’s first album, “A House of Many Rooms: New Concert Music by Fred Hersch.” Fred practiced mindfulness meditation for 20+ years and has taken it as a point of inspiration for numerous compositions, including recent albums “Breath By Breath” (2022) and “Silent, Listening” (2024). His 2006 album “Leaves of Grass” takes up the famed Transcendentalist work by Walt Whitman.

Pauchi Sasaki, the composer of the fourth piece, “Mother’s Hand, Healing Hand (엄마손은 약손)” (2021), is well-known for pursuing experimental, interdisciplinary, and multidisciplinary approaches, often incorporating multimedia and mixing digital and acoustic musical sources. This particular work overlays a spare acoustic trio for piano, violin, and cello — performed at the salon by Eunbi with guests Pala Garcia (violin) and John Popham (cello) — with electronic sounds and samples of a recording of Eunbi and her mother softly singing a traditional Korean chant, “Mother’s Hand Healing Hand.” Eunbi says, “That’s something she sang to me growing up whenever I was sick because in Korean culture, we believe that mothers have these healing powers for their children.“ For me, the tone of this piece is so gentle and luminous, with a sprinkling of powerful bass notes that root it and remind the listener how a mother’s love runs immeasurably deep, perfectly befitting the track’s title.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamIn January, I attended a “Women Artists as Parents” talk at the Chamber Music America national conference. Eunbi served as one of the panelists. There, too, she shared that her experience of becoming a parent has strongly influenced her spiritual development and creative direction. Both Eunbi and Pauchi have sought to de-compartmentalize music-making and parenting. Rather than seeing them as in conflict, they embrace those roles as seamless and complementary, nurturing one another and serving the same higher purpose, manifesting both within their relationships with their children and through the experiences they facilitate with audiences.

Pictured L to R: Rebecca Fischer, Eunbi Kim, Midori Larsen

In the composer’s note by Pauchi in the album’s liner notes, Pauchi states, “I find myself constantly telling my son how much I love him. I think this impulse comes from the realization that he won’t remember his early years, a time when his parents loved him so much and took care of him with all of their energy. Subconsciously, maybe I want to engrave my love for him through sound somewhere in his cells, so he can somehow remember these years. And, in a way, that’s the power of lullabies: mothers engrave their voice in the heart of their babies, becoming the most needed and healing sound for every human being. Even if time and oblivion affect our memory, sound will always bring us back to our primal bound and love.”

For her “Deep Listening” gathering on May 19, Eunbi introduced and led the audience in a Deep Listening® exercise created by Pauline Oliveros (1932 – 2016) called “Tuning Meditation.” A highly influential figure in post-war experimental and boundary-dissolving music who was awarded four honorary doctorates and profoundly influenced even other luminaries such as John Cage, Pauline described her Deep Listening® practice “as a way of listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what you are doing. Such intense listening includes the sounds of daily life, of nature, of one’s own thoughts as well as musical sounds” (from Pauline’s website).

In summary, the Tuning Meditation is a group exercise that asks participants to vocalize repeatedly whatever tone comes to mind. At first, most everyone tones different notes. For subsequent tones, participants are instructed to match the tone of another participant or to vocalize a different note. For a while, it seems like the exercise will go on like this endlessly, sounds arising and ending at different times, with some notes matching and some not. But amazingly, at some point, without anyone consciously trying to accomplish anything, the sounds grow more harmonious, and suddenly, everyone falls silent together.

It is said that if one starts a bunch of mechanical metronomes at different times, they will eventually synchronize, as will the heartbeats of a mother and her baby when the mother holds her baby to her chest. This exercise is something like that. All of us in the room listened deeply to one another and to ourselves simultaneously, with no agenda, and we experienced ourselves coming together. It was a beautiful and healing experience.

Eunbi performed “Saturn Years” for us twice, before and after the Tuning Meditation, and asked us to share what, if anything, had changed. We had changed. After the meditation, we listened more deeply and felt more intensely. At the same time, we noticed other sounds in the room. And even though each person who spoke shared a distinct impression, I think we were excited to discover and affirm that we had all experienced a heightened state of awareness. Had the music itself also changed? Had the meditation, or its effect on us, changed how Eunbi played it? I’m not sure since we ourselves were hearing it differently. At the very least, I think she felt more connected to us.

All in all, this was a unique experience. Eunbi made connecting through deep listening her theme and designed a musical program that enabled everyone in attendance to explicitly experience connection through listening and understand how and why. Similarly, at her gathering “How to Love,” Eunbi shared musical material that explores how she has experienced love and relationships throughout her life in a way that invited those present to reflect on how we experience our own relationships. Both programs offered fresh and exciting music and tools for becoming more present, joyful, and compassionate.

Eunbi’s Artist Fellowship at NAC runs through the end of the year, and I look forward to discovering what kind of transformative experience she will create next. If you would like to follow her, you can find her on most social media, most regularly on Instagram. Her music is available on all major platforms.