This post is also available in:

English (英語)

Binh Thuan: Another Imagination of Death

by Hai Yen Ho| November 9, 2025 | Literature

Photo © by Hai Yen Ho

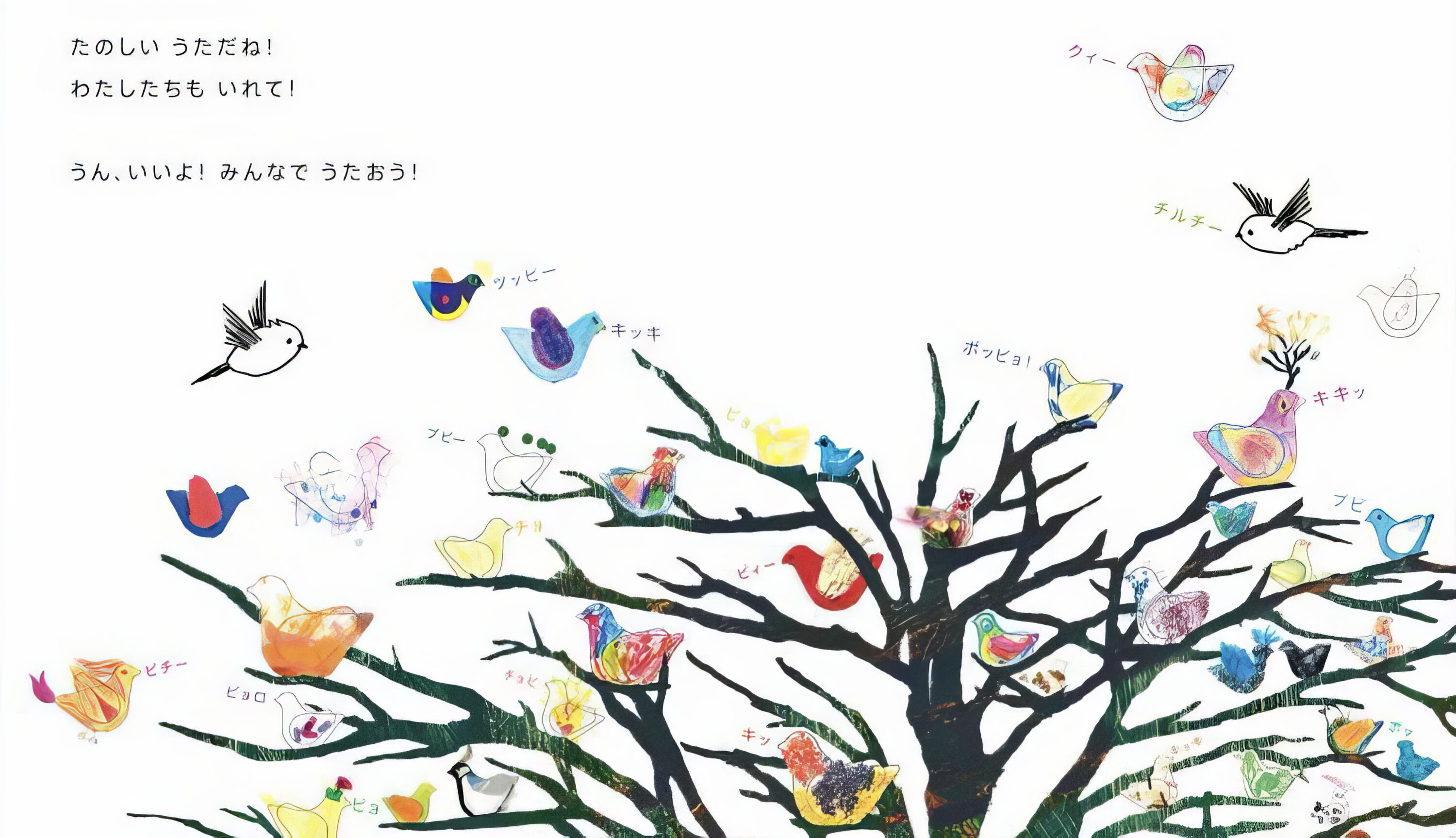

Photo © by Hai Yen HoAmong the countless fragments of memory vying to become the most precious, the one that lingers deepest within me is of a morning by the sea. In that fragment, I see myself sitting in a small coracle, watching an old starfish struggling in its quiet encounter with death. Its five arms fluttered faintly on the water’s surface, each tremor sending ripples through its frail body. The weight of its form pressed against the wet sand beneath, birthing tiny bubbles that swelled, shimmered, and burst one after another. Darkness seemed to pulse — swelling and sinking — at the place where the creature met the sea. Soon, as the tide withdrew, it would be left bare, exposed under the fierce cascade of tropical sunlight. Its body would begin to dry; the tentacles, stretched helplessly along its five arms, would soften, then slowly collapse in exhaustion, until movement ceased altogether, and it surrendered, entirely, to a fate long foretold.

It was the summer of 2021, when a storm had just swept through Bình Thuận, claiming the lives of three fishermen. In the faint unease that followed as I read the news on my smartphone, images of fishermen staggering against the wind rose vividly before me. I rarely read such stories—my social media feeds are carefully set up to show only what relates to my work, and I stop scrolling once that quota is met. A storm, a few lost fishermen, in the most literal sense, did not belong to the realm of my daily concerns. But that day, the headline appeared on my screen, and I knew I had to do something. A few quick calls. A transfer message. A dawn train. Hours later, I arrived in Bình Thuận, a place still bruised by the storm. Life had resumed its rhythm, calm, quiet, yet something within it remained broken, unhealed.

“After the storm, the sea is always calm.” The phrase echoed suddenly in my head—the kind of hollow philosophy favored by those who bury themselves in books, music, and films, rather than setting foot in the real world, like I do. Had it come from an old fisherman, weathered and wise, perhaps it would have carried a different gravity. But this was only me, spurred into motion by a headline weeks old, mistaking impulse for courage, tragedy for romance. Yet what is romantic about death? Of all the world’s so-called romantic notions, death is perhaps the least deserving, yet the most embellished. Death means a few tens of millions of VND for funerary rites, and a few tens more for a burial plot, unless one chooses the fire. Death means a body surrendering to decay, to worms and the dampness of soil, or reduced to a handful of ash under the blaze of flame. Death means leaving behind the burden of making a living for others, and that may be an aging mother, a frail wife, or small children. There is nothing romantic about that. Not here, in this poor fishing village, where the word “death” carries a weight that crushes all else.

The afternoon before I captured the image of the starfish, the one that would remind me of death, I found myself clambering through brambles, scaling slick boulders. In the distance, fishing boats clustered together, rocking gently in retreat. The air was filled with a chorus of inconsequential sounds: children’s laughter, a few scolding adults, the growl of a motorboat slicing toward open sea, the crash of waves, the rush of wind, the cry of circling birds. I had brought nothing but a camera, as if it were something that could serve as a weapon, a currency, or a compass should I lose my way. Yet that entire afternoon, and the morning that followed, I took no photographs. I only remember climbing up and down the rocks, dipping my feet into the warm pools of seawater collected in crevices, then burying them in sand. The camera strap wound tightly around my wrist, layers of canvas and suede forming a strange, makeshift bracelet.

Photo © by Hai Yen Ho

Photo © by Hai Yen HoThe fishing village sat at the edge of the rocky shore, growing livelier as it neared the harbor. When I arrived, it was still quiet, suspended in the hush of day’s end. A few young men called out teasingly from a tattered shack patched together with tarpaulin and branches. Nearby, an old woman crouched over a small fire, burning trash, nylon, fish bones, and shells releasing a thick, acrid smell that mingled with salt, dead fish and garbage. On the sand, women spread nylon sheets and displayed their modest catch, their skin pale and wrinkled from hours in water, dressed in thin floral garments, heads shaded by conical hats. The scene was languid, drained of vitality, even the flies buzzing about seemed too weary to be swatted away. Farther off, the boats had been pulled ashore, covered in tarps, waiting for the next voyage. Most of the gear was gone; only puddles of brackish water, bits of sand, and a few small fish remained. The boats, large and small, long and round, were told apart by the eyes painted on their bows. Some large, some small, some with intricate pupils, others just a crude black dot. Yet whether fine or rough, each pair of eyes saw its way through the sea, guiding its vessel away from the abyss. They were meant to fool the creatures of the deep into mistaking the boats for monsters, much like Western sailors once placed figureheads at their prows, the talismans to guard them from storms. Of course, no charm can truly fend off disaster, and even the surest course can be lost, but faith is something all must have. For those who live by the sea, whose lives and livelihoods are at its mercy, faith is the one thing that keeps them afloat.

That day, I had only meant to take a short walk before returning to my lodging, a humble seaside house, its walls lined halfway with patterned cement tiles, looking out to a weary little garden. Coastal homes often share that curious trait: the richer ones tiled from floor to ceiling, the poorer only halfway, as if to expand the smallness of their bathing space. Perhaps it is because their walls and floors are always damp—wet from the green fishing nets pulled in after long days at sea, from the buckets of fish left unsold after a failed bargain, or from the feet of children who, despite constant scolding, still run barefoot through saltwater and sand. I tucked my camera away, showered quickly, and stepped out to have dinner, a simple one with a plate of rice and fish in a small roadside eatery that seemed to serve only the locals, since tourists rarely ventured this far. I needed to eat early, sleep early, because at midnight, I would embark on my first-ever fishing trip in a coracle.

At the time, and for long after, I didn’t realize that night would become one of the most precious memories of my life. In those days, when I was still caught in the limbo of figuring out how to live my own life, that fishing trip carried an inexplicable significance. What began as unease while sitting with two male strangers I had met only hours before soon gave way to quiet exhilaration as we drifted into the vast silence of the nocturnal sea. Even if I summoned every word I know, I doubt I could truly capture that sensation—the unsystematic harmony in the sense of weightless impressions as my body swayed from side to side with the tide; my eyes adjusting to the dense, velvet darkness pierced only by the flicker of lanterns across the water; my ears listening to the steady crackle of burning coal mingled with the soft rhythm of waves tapping the hull; my nose felt the faint sting of engine oil hung in the air. At times, I thought I might have dozed off within that surreal trance, though my hands still released and pulled the nets, waking only when the ropes came taut, droplets of seawater tracing cold, stinging paths down my legs, mingled with the metallic scent of fish and seaweed. Back then, I hadn’t traveled much, but I had trained myself to adapt to whatever life presented, to trust those around me, especially when trust was the only choice available. I was standing, at that moment, between difficult decisions, caught in the realization of how raw and unforgiving the world I worked in could be. That impromptu journey—harsh, spontaneous, yet strangely healing—opened something new in me. It was my first truly conscious act of aimlessness, and it succeeded not because it ended in glory, but because it left behind a dream that would linger through all the years of wandering to come.

Before that night, I knew nothing of how fishermen lived, about their coracle, tangled nets, anchors, flags, buoys, endless coils of rope. I hadn’t known that many of them couldn’t swim, perhaps out of sheer weariness of the sea that had both raised and betrayed them. Nor that women were forbidden to board boats—a superstition, they said, of bad luck. Women of the coast remained on land: sorting, gutting, selling fish, mending nets—their hands steeped in salt and scales, their bodies perfumed with the persistent scent of death. That night, then, was more than a personal experience—it was a rare privilege, a quiet rebellion, something even women who had lived by the sea their whole lives might never know.

That voyage, in its own way, mended a fracture within me. It tied a fragile thread between my life and the world. A night of silent, seamless rhythms—the nets cast, the anchors dropped, the fish caught and freed, all moving in harmony. A kind of work that requires no conversation, no aesthetics, no creativity, nor the polished poise my own profession demands—all of which are useless here. What matters instead are silence, endurance, the strength to bear the cold, and the ability to decide without hesitation—qualities, I believed, I possessed in greater measure. I relished the hush of the sea, the soft struggle of the fish, and the moments when H., the fisherman, would break the silence with a song—only to fall silent again, mid-verse, as if lost in thought, before continuing with another line that had nothing to do with the first.

—

“When a squid is dying,” H. said softly as he watched me cradle a small one in my palm, “its body begins to bloom with red spots. The more you touch it, the faster they appear, like tiny signal lights.” The creature lay limp, its strength draining away. It was too small. Its skin shimmered translucent gray, and the red spots began to flicker, at first a few, then many, pulsing across its body like a constellation. They did look like the signal lights that fishermen hang from their boats as beacons in the dark. I shouldn’t have held it; it had no value. But by then it was already half gone, and returning it to the sea felt like an act of quiet absolution—for me more than for it.

The wind still blew. The sea still hurried. I hauled the net, a hundred meters long, dragging the whole ocean through its dripping strands. The air grew colder. H. cheered when three sardines thrashed in the mesh. This was our third throw of the night, after two fruitless ones when the net snagged on the reef below. We had gone out early, past midnight. Few fishers tried such hours; the sea was still calm, though it felt wilder than any I’d known. Paradoxically, rough seas yield richer catches. H. told me many who perished at sea did so chasing those tempestuous days. One of the men lost in the recent storm, he said, hadn’t drowned offshore at all but died on land—struck by his own boat as he tried to secure it during the gale. A few million VND’s worth of fish for two lives. A small coracle for another. The exchange was obscene in its simplicity. How cheap a human life can be, I thought. Too cheap to bear.

The night flowed on and the sun still slept somewhere beyond the ocean. I sat quietly as H. crouched by the small stove to grill our catch. The fish—silver scales peeling away—sizzled in a cut plastic canister, turning black and fragrant. Smoke curled upward, lingered, then vanished into the dawn air. It was a moment of wonder. The sky was no longer black but washed with colors—blue, rose, lilac—shifting from dark to pale as if an unseen hand kept stirring the light. Everything grew clearer. I saw the painted eyes of distant boats returning from their night at sea. The first rays splintered on the waves. “Twilight and dawn,” H. murmured, “those are our hours to sail.” I felt then as though I had just crossed an ocean, though in truth, we had been gone no more than five or six hours, never far from shore. It was the simplest kind of fishing here—meant for solitary men on calm nights. I looked down at my feet: the catch was small, but perhaps, that was never the point of the journey.

Photo © by Hai Yen Ho

Photo © by Hai Yen HoAs sunlight spread slowly across the sea and H. strained to drag the coracle ashore, my mind lingered on the fish—those already caught, and those yet to be ensnared. I thought of the little round coracle that could sustain a fisherman’s life, yet had taken the lives of others. Not far away, a hollow in the sand released tiny, glimmering bubbles that caught my attention. Stepping closer to the water’s edge, I realized what it was: a large starfish, its stubby, bamboo-like arms writhing feebly on five thick limbs—one of those wild sea creatures I had never before seen alive, now struggling in vain to right itself, to reach the surface once more. It couldn’t. Its five arms beat against the wet sand in helpless rhythm. The coracle scraped and hissed as it was hauled higher, the morning sun blushed orange and pink, deepening toward the horizon—everything compressed into a single, heavy moment that seemed to carry an obscure, dreamlike meaning, like those dreams where a finger presses against silent lips before pointing toward something unseen, leaving the dreamer startled awake before they can comprehend what it was.

And though I would later forget the details of that strange fishing trip and my aimless wanderings through the coastal village, that morning remained. The sound of the coracle scraping sand, the dying starfish, the rising sun—all fused into the first image that came to me whenever I thought of fishermen, of life at sea, or of death itself.

I stepped forward, turned the starfish over, and threw it back into the waves.