This post is also available in:

日本語 (Japanese)

I was excited to explore Kyotographie, the sprawling annual international photography festival in Kyoto. Now in its 12th year, it has become one of Asia’s largest photography festivals. It features 13 curated main exhibitions and more than 100 KG+, KG Select, and Special exhibitions installed in venues large and small all over Kyoto.

As far as I know, there is nothing like it in NYC. We have the annual AIPAD show, but it primarily consists of works selected by participating galleries, which must rent their booths and sell the works they display to justify the high cost of attending. While some participating galleries are more curatorially- or mission-driven than others, the photographs on view are mostly selected for their commercial appeal rather than for purely social or aesthetic impact.

Kyotographie is refreshingly different and much more inspiring! “We always aim to highlight the richness of both local and international talent. By highlighting many regions and people we can offer a dynamic and inclusive festival which connects and elevates everyone,” say festival founders/organizers/life partners Lucille Reyboz, a photographer from France, and Yusuke Nakanishi, a Japanese lighting artist.

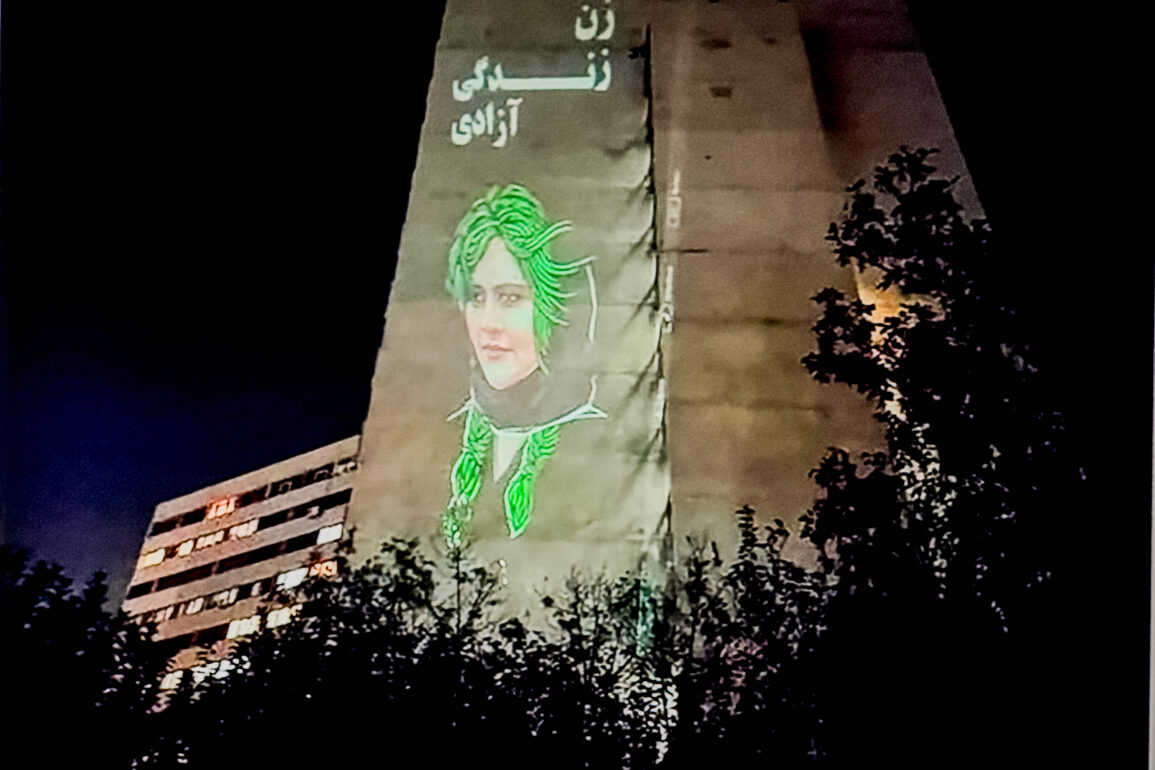

One of the exhibitions I was most keen to visit was “You Don’t Die — The Story of Yet Another Iranian Uprising,” an exhibition at Sfera culled from 1000s of mostly anonymous images of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising inside Iran, collected and authenticated by Le Monde photo editor Marie Sumalla and Le Monde journalist Ghazal Golshiri. With the assistance of Iranian colleagues Payam Elhami and Farzad Seifikaran, they established the date and location of each photo. Photographs by several professional Iranian photographers inside Iran also appeared in the exhibition.

As a feminist and a Sufi Dance Artist with teachers and friends from and inside Iran, I had a strong personal interest in the uprising and in this show. During the pandemic, one of my Iranian-born staff members at CRS was forced by circumstances to return to Iran, and communication with her became more difficult after Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a 22-year-old young woman from Saqqez, in Kurdistan, western Iran, was arrested on September 13, 2022 by the “morality” police (Gasht-e Ershad) while visiting Tehran with her brother because a single strand of her hair had come loose from under her headscarf. Mahsa was loaded into a police van and severely beaten, dying in police custody at the hospital three days later.

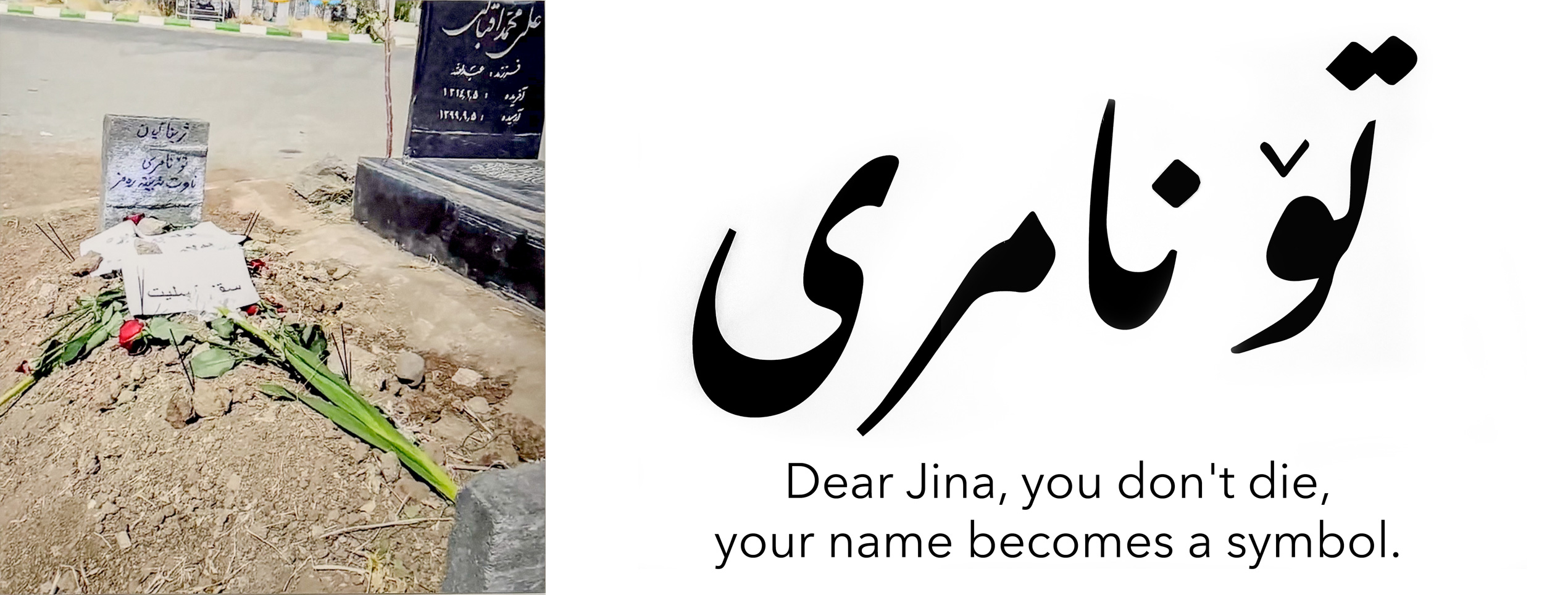

At Mahsa’s funeral, a plain block of concrete was placed on her grave, on which her uncle painted the words (translated into English here): “Dear Jina, you donʼt die, your name becomes a symbol.” Images of the gravestone bearing these words were posted on social media — the first known of which appears in this exhibition — and resonated with young women all across Iran, who were fed up with having to live with the sexist restrictions and capricious violence inflicted upon them by the government and who understood that what had happened to Mahsa, through no fault of her own, could easily happen to any of them at any time.

Photo © by anonymous photographer

Photo © by anonymous photographer“Near, Jina, you don’t die, your name becomes a symbol.” September 17, 2022, Iranian Kurdistan

From that point onward, more and more women inside Iran, at first young women and then joined by women of all ages and social classes, started to walk outside without their headscarves, and even men began accompanying them in solidarity, sparking what became known as the “Woman, Life, Freedom!” movement.

Images of the protests and the violent police crackdowns, as well as images created in support of the movement, filled social media, rapidly amplifying and spreading the messaging. The number of people joining in the protests quickly swelled. Within days, the Iranian government began restricting access to social media. Nevertheless, people still found ways to share many images of these courageous protesters and the vicious crackdown they endured, and coverage of the uprising spread around the world, inspiring numerous protests and events in solidarity. This exhibition seeks to reflect the breadth and spirit of what has been, in the curators’ words, “the most powerful wave of protest in the history of the Islamic Republic of Iran, established in 1979.”

This simple and direct cry of “Woman, Life, Freedom” arises out of the very specific conditions inside Iran, the only country other than Afghanistan where women are required to wear hijab at all times in every public space. I am not qualified to explain all of the nuances of Iranian political history, nor is this the place, but it may be helpful to preface my remarks on this exhibition and this movement with a brief summary of relevant events preceding it.

The 1979 Revolution was a response in large part to corruption, political repression, economic inequality, and Western influence under the previous Pahlavi dynasty. This dynasty had ruled Iran since 1953, when it took power in a coup supported by the United States to keep Iran out of the Soviet sphere of influence. Support for the 1979 Revolution was widespread. In a national referendum, the citizens voted overwhelmingly in favor of establishing a new “Islamic Republic of Iran.”

However, many members of society supported the revolution for many different reasons. The nation had been quite secular for decades. Hijabs and other traditional head coverings were largely unpopular and seen by many as backward. While some partisans of the revolution had explicitly declared that the institution of Islamic law was their goal, others rebelled with different aims in mind and, indeed, did not want or expect a strict implementation of Islamic law or a requirement for women to wear hijab.

As I understand it, many Iranians were, in fact, shocked and outraged when the Ayatollah Khomeini announced, after returning from exile and assuming the role of Supreme Leader of the new government, that women should observe the Islamic dress code. Large protests took place for six days until the government assured that the dress code was only a recommendation. Nevertheless, over the next several years, laws requiring hijab were gradually implemented, and those who did not comply were subject to arrest, severe beating, and imprisonment.

Since then, movements have periodically arisen within Iran calling for a broader representation of the spectrum of political voices inside Iran within the government and a relaxation of some of the restrictions. Each time, those speaking out have been violently repressed and their movements crushed. There are elections in Iran, but the Islamic mullahs (religious leaders) only allow candidates of their liking to run. Despite enduring decades of sanctions from the West and anxieties fueled by the near-constant threat of war with Israel and other regional neighbors, the Republic still manages to export enough oil and raise enough money to keep economic pressures somewhat at bay and to generously pay its enormous religious police force to enforce its draconian rules and maintain power.

So, the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement arose out of the particular history and circumstances within Iran. At the same time, the slogan clearly resonates with women and people of all genders all over the world. In New York and throughout Europe, the many exhibitions and demonstrations taking up this slogan are proof of that. I was nevertheless a bit surprised, and thrilled, to find this exhibition at Kyotographie at a time when the international news media have largely moved on to other stories.

And I didn’t expect to find such a movement given a major spotlight inside Japan. After all, Japan ranks only 118th out of 146 countries in gender equality. Apart from the large rallies against nuclear power in the wake of the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster, demonstrations in Japan, particularly those in solidarity with movements originating in other countries, have tended to be small in recent decades. It is a credit to the organizers of Kyotographie that the festival includes this exhibition and several others that explore human rights and political issues.

Seeing the video and images here of women standing out in the open, in crowds, with hair uncovered and blowing in the wind, and knowing that this act, one of simply…being…, can lead to arrest or even death on the spot, makes my own hair stand on end. It is enormously inspiring. It takes such courage. It communicates that you can take my life, but you will not limit my spirit.

They risk their lives without any recognizable hope that it could lead somehow to a change of government and better lives for those who survive. I am reminded of Lesson 153 from A Course in Miracles, “In my defenseless my safety lies” and Lesson 199, “I am not a body. I am free.” Or, as Mahsa’s uncle wrote on her gravestone, “You don’t die.” It’s up to us to ensure that their stories and their spirits outlive their bodies.

The exhibition brings together and blurs the line between documentary photography and staged photographs that were shared, sometimes only temporarily, to amplify the voices of the movement.

In the photo below, posted without photo attribution on October 26, 2022, the 40th day after Mahsa Amini’s death, we see a young woman without a hijab standing on a vehicle while a huge crowd of people pass by her to visit the Aychi cemetery in Saqqez, Mahsa’s hometown in Iranian Kurdistan, where Mahsa is buried. The crowd is traveling there to commemorate that anniversary, which is known as the time when the soul passes to the afterlife. Did the anonymous woman know she was being photographed? Was the photo planned? Or did someone simply catch a spontaneous moment? It seems to me that it doesn’t really matter. Either way, the woman risked her life to express her solidarity. Either way, the image is authentic and powerful.

Photo © by anonymous photographer

Photo © by anonymous photographerThe crowd’s presence indicates the wide support for Mahsa. So does the fact that no one is trying to harass or arrest the woman whose hair is uncovered. Still, she is taking a risk. If she had been photographed from the front and the authorities had obtained the photo, she might have been identified and punished later. And maybe she was…but she wasn’t going to be stopped.

The freedom and power of the photo is undeniable. It calls to mind the iconic Adbusters poster of the ballerina atop the Wall St. bull statue that kicked off the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement and the even more indelible image orchestrated by the Yes Men of the man dressed as a matador who poses atop a police car taunting the bull in the middle of the OWS demonstrations while the police, backs to him, are distracted by two men dressed as clowns. All three of these images use a single figure standing tall to convey freedom and symbolize the collective spirit of an entire movement. But the image from Iran is the most compelling of the three because only the woman in the Iranian image is risking her life to express herself and because she is claiming something beyond policies or politics, the fundamental right to freedom. And I think the many women inside Iran who saw this image and others showing women uncovered in public could not only relate but could imagine what it must feel like to feel the wind at last in their hair. These images activated the long-repressed longing to experience the same freedom and emboldened women throughout Iran to claim it.

On December 31, 2022, the professional photographer Elham Abbasloo photographed herself with not only an uncovered but shaved head, lying curled upon a bed of clippings of hair that many other women had given her, illustrating another form of rebellion that has become common inside Iran. A woman’s hair has long been considered an important symbol of beauty. The requirement to cover it has come and gone throughout Iran’s Shia history, and the tradition of cutting one’s hair as a form of protest and/or mourning can be traced back at least to the Persian epic poem Shahnameh by Ferdowsi, written between c. 977 and 1010 CE. But the act also references and inverts the Old Testament story of Delilah cutting Samson’s hair to disempower him. Women, by cutting their own hair, are claiming their power.

Photo © by Elham Abbasico

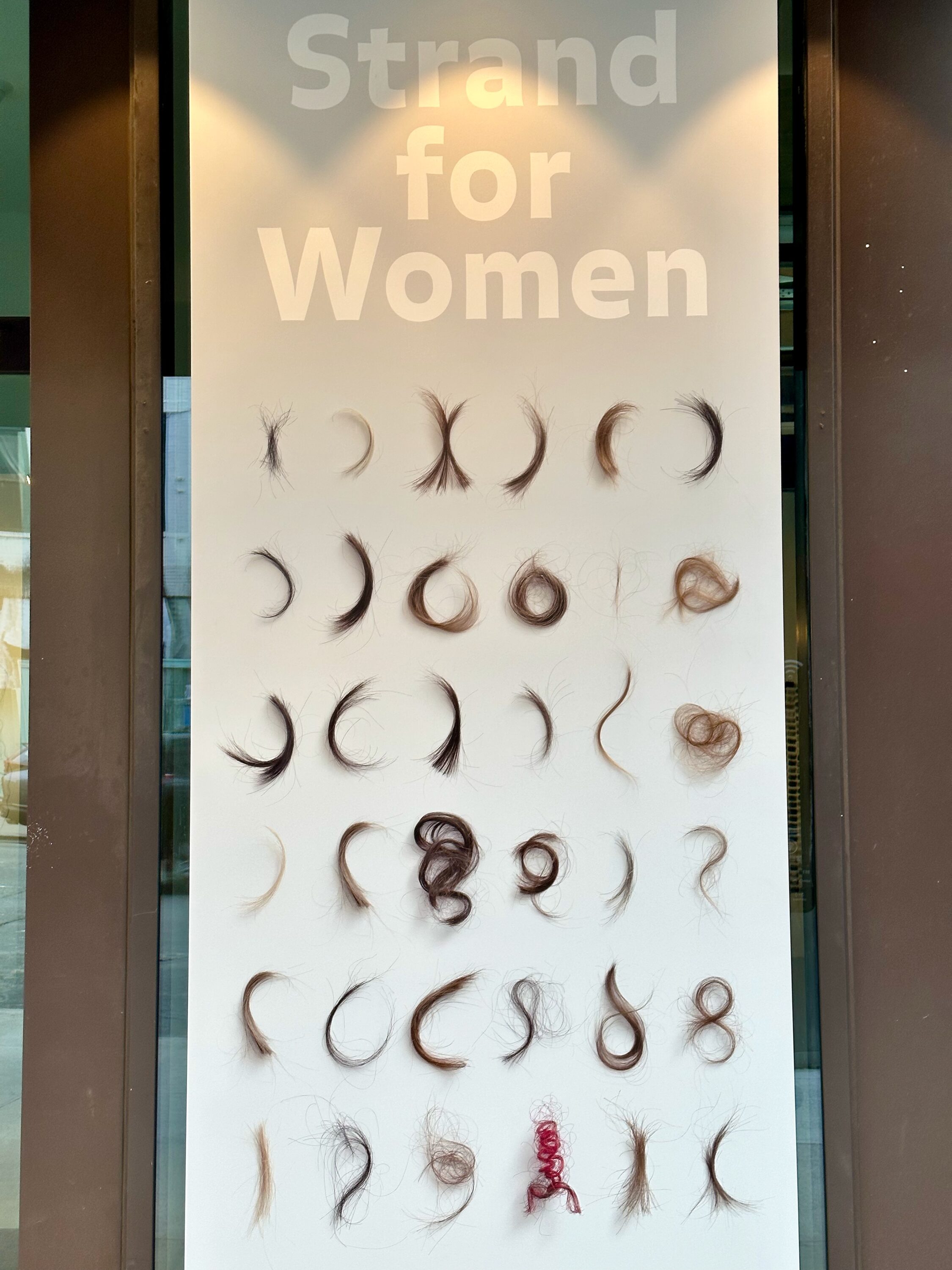

Photo © by Elham AbbasicoIndeed, women worldwide began cutting their hair in solidarity and posting photos under hashtags like #hairforfreedom. In New York, the FIAF and the artists Homa Emami, Shirin Neshat, Prune Noury, and Cima Rahmankhag organized the exhibition Strand for Women.

Inside the exhibition, Cima Rahmankhah’s large abstract drawings of hair neighbours Shirin Neshat’s video installation “Sarah” with a woman’s face and hair floating in water. Hanging on a wall, the incredible hair chain object by the artist Homa Emami consciously refers to the current feminist women’s revolution in Iran. Every year, women’s hair grows by about 15 cm, and after 44 years of oppression, the result is a 660 cm long hair.

Visitors can also contribute to a collaborative artwork on a giant wall made of thousands of hair strands – sent over the past month by people worldwide. As Iranians are asking for everyone in favor of democracy, everyone in favor of women’s rights, to bring light and attention to their important fight, Prune Nourry answered this urgent call with another call: she asked for hair strands, a medium consistent with her artist practice, as she started to collect strands from people who inspire her in 2007. — Strand for Women

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher PelhamThe exhibition, which I also attended, opened on International Women’s Day, March 8, 2023, harkening back to the March 8, 1979, protest by thousands of women inside Iran in response to the Islamic Republic Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini’s pronouncement that women should wear the hijab in public.

The exhibition notes state that “#WomanLifeFreedom movement is inspiring. It is universal. Hair is an essential element for ignition. A strand (wick), can be extinguished if neglected, or can ignite a fire. We hope this exhibition ignites our collective communities as we #StrandForWomen.”

Despite the enormous sense of solidarity and empowerment that the protesters inside Iran have experienced, the government’s repressive behavior has not subsided. And in fact, the violence has escalated, and the protesters’ determination co-exists with a sense of hopelessness. My staff member and her family have lived under this constant dark cloud. They fear that the storm clouds might burst at any time, raining terror down on everyone. Many feel that perhaps only war can lead to change, and war brings its own horrors and is not something they wish for.

Nevertheless, they persist. No one inside Iran under the age of 30 has known anything but repression. Many would rather die than continue living in this way. Love keeps them going. Though unarmed, the participants in the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement demonstrate great spiritual power, for they can touch the spirit in each of us and remind us who we really are, awakening our own strength and courage. And I believe they feel that. It would seem to take a miracle to bring down this well-armed and well-formed government, but it is said that love can accomplish anything. Let’s see it realized together. Can we hear their call and accept anything less of ourselves?

This short film, following the journey of our book Woman Life Freedom, captures this historic moment in artwork and first-person accounts. It is both a universal rallying call and a celebration of the women the regime has tried and failed to silence.

This is what protest looks like.

Woman Life Freedom: Voices and Art from the Women’s Protests in Iran is edited by Malu Halasa (Saqi Books, 2023).

This short film was directed and produced by Saqi Books, with thanks to Arts Council England, Truthdig, The Markaz Review, K.B Bishara, Naomi Shakespeare and audio actor Beth Em.

Featuring artwork by Shiva Khademi, Soheila Sokhanvari, Tahmineh Monzavi, Alexander Cyrus Poulikakos, Niloofar Rasooli, Pamela Karimi, Khiaban Tribune, Iranian Women of Graphic Design, Roshi Rouzbehani, Marziyeh Saffarian, Milad Ahmadi, Mana Neyestani, Tasalla, Hengameh Golestan, Mehri Rahimzadeh plus many others.

Woman Life Freedom is dedicated to the women and girls of Iran. — Saqi Books