This post is also available in:

日本語 (Japanese)

Facing Death, Finding Oneself at UrBANGUILD, Kyoto (April 16, 2024)

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

After a couple of days taking in the scenic wonders of Nagano — including a breathtaking night viewing of the cherry blossoms at Ueda Castle, the one-of-a-kind octagonal pagoda of Bessho Onsen, and the famed Snow Monkey onsen — I took the Shinkansen down along Lake Biwa to Kyoto where the Kyotographie international photography festival was taking place. I’ll cover that in future articles.

On my first night in Kyoto, I attended FOUR DANCERS vol281 at UrBANGUILD, a cafe/bar and multidisciplinary performance space in the heart of Kyoto. Like an old-school club on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, it’s dark, grungy, and covered in flyers. UrBANGUILD presents a wide variety of younger and older artists and draws an extremely diverse audience as well, making it a beloved oasis for contemporary and experimental performing artists in the otherwise more traditional and conservative-minded Kyoto.

Nearly all the artists I met on this trip were new to me, yet many had worked with artists I knew personally. The experimental/contemporary art scene extends in all directions: geographically, thematically, and stylistically. And it’s not exactly a small world, but I find that it’s extremely interconnected. Artists, like bees, are constantly exploring and often travel, seeking audiences and inspiration. Art, if it resonates, cross-fertilizes cultures in ways that may not be evident unless you’re looking for those influences.

I came to this program to see two artists in particular whom I had heard about but never seen perform, Chizuko Kotani / 小谷ちず子 and Miwako Inagaki / 稲垣美輪子. I’d met Chizuko many years ago in NYC and found that dancer/choreographer Takemi Kitamura, whom I had presented once in NYC, had studied with her in Osaka. My translator for the evening, Akiko Furukawa, a dance colleague who had once lived in NYC, had worked with Miwako previously.

Although I wasn’t familiar with the other two acts on the program, I learned that they also had interesting connections and stories. Luan Banzai is from Brazil but has lately been living in Kyoto. Better known for creating animation and visual art, here he mixed ruminative movement elements — sitting and thinking, reclining, posing theatrically — with startlingly frenetic dance sequences in a long solo that repeatedly surprised and delighted the audience. On this night, a diverse group of foreigners came to support him, which I take as evidence of the existence of a sub-community of foreign artists in Kyoto.

The fourth piece on the program was offered by the duo of Haruna Ueno / 植野 晴菜 and Riryong Ko / 高梨玲. They first met last year at Yukio Suzuki’s dance creation workshop in Matsuyama, Japan, and they became intrigued by how they might bring their disparate dance styles together. Not only their dance training but their upbringing also had been completely different. Haruna told me that, if not for dance, they likely would never have crossed paths. In public discourse, artists are often lumped together as if they are all bohemian restaurant workers, except for a few celebrities. In fact, anyone at all can create, and artists come from every walk of life. Moreover, the arts bring people from all walks of life together.

Haruna and Riryong wondered, with so little common ground, what they could possibly produce if they collaborated, without one following the other. What might the result look like onstage? Could a fruitful and intimate, yet non-hierarchical and free relationship be possible? Could that situation itself be taken as the theme and expressed onstage?

Haruna was born and raised in Japan and studied ballet, musical theater, and double Dutch in her youth and then performing arts theory at university. After graduating, she participated in Dance Box‘s domestic dance study abroad program and participated in works by Kota Yamazaki (with whom I worked in NYC when I commissioned his wife, Mina Nishimura, in 2010), Zan Yamashita, Shintaro Hirahara, and Chie Ito, exposing her to a variety of contemporary, conceptual, and butoh-based somatic practices. More recently, Haruna has studied with butoh artist Masami Yurabe (as has Miwako Inagaki).

Riryong grew up studying Korean traditional dance, spent her high school years in New Zealand, and then, in college, discovered Gaga, a contemporary dance technique created by Batsheva Dance Company Artistic Director Ohad Naharin. Rather than using a particular vocabulary of movements and body shapes, Gaga uses instructions and images to guide dancers to experience a heightened sensory awareness and understanding of their bodies. Riryong was so taken with it that she traveled to Israel where Batsheva is based to further her studies.

In their duet, Riryong and Haruna gave themselves the same tasks but not the same choreography. Each carried out the tasks in different ways or at different times and moved according to their individual styles and habits, allowing their differences to be visible to the audience. Nevertheless, there were times when they seemed to influence one another and become more connected. I feel they succeeded in expressing intimacy while maintaining independence. While time constraints do not allow me to write more about their work here, I will say that the presence of these three artists on the bill made for a varied and engaging evening.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Luan Banzai at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, 4/16/24

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Haruna Ueno and Riryong Ko at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, 4/16/24

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Luan Banzai at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, 4/16/24

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Haruna Ueno and Riryong Ko at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, 4/16/24

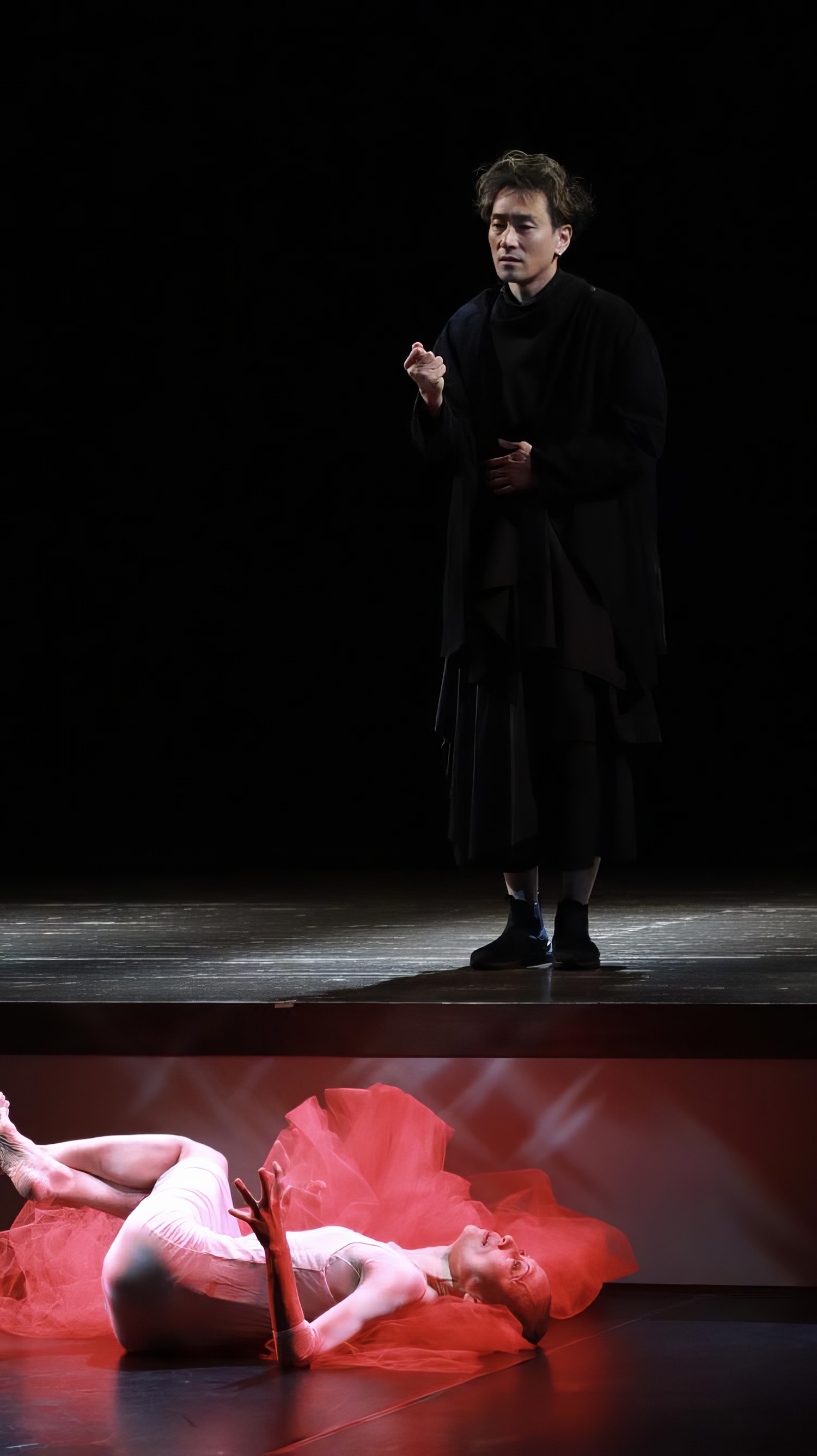

Chizuko Kotani and Hajime Totani

Chizuko, who has trained generations of younger dancers in Japan, began dancing back in the 1970s under Miyoko Fujiwara. Miyako became ill soon after and organized some final concerts in the hospital where she was being treated, which made a big impression on Chizuko. Miyako passed, and Chizuko took over running the studio at age 21 and founded her own company, Dance Core Possible, in 1981. Chizuko also studied Martha Graham technique with the late Akiko Kanda and bases much of her movement on this foundation.

To further trace out the cultural influences, it’s worth pointing out for those who don’t know that, while in college, Akiko Kanda saw a performance by the Martha Graham Company during its 1955–56 tour of Asia and promptly dropped everything and moved to NYC to study at Graham’s school, an incredibly bold act. She soon became one of Graham’s principal dancers, performing in her work for four years to great acclaim before returning to Japan, where she, in turn, inspired innumerable girls to enter the field of modern dance, becoming the most influential and highly honored modern dance artist in the history of Japan.

The Martha Graham Company toured Asia at that time at the behest of the US State Sept., which hoped that sponsoring cultural outreach programs such as this would help counter the spread of communism. Graham always stated that she was not political, and her works did not tackle explicitly political subject matter, yet she embraced this informal role of US cultural ambassador. At the same time, her work of running a community dance school and professional company made up of primarily female dancers was inherently radical. One can’t help but see the irony in how the US government sought to use artists to promote freedom (conflated with capitalism) abroad while at the same time blacklisting numerous artists at home for having suspected communist sympathies or simply for being radical. Nevertheless, the seeds of art and, by extension, transformation were spread.

Akiko Kanda adopted Graham’s technique and, perhaps more profoundly, dance as a way of knowing oneself, a way of living and experiencing and understanding, but then used that to create works that looked very different from Graham’s. Kanda’s choreographies were many and diverse, at times incorporating elements of Noh and other Japanese traditions. While Graham denied being a feminist, Kanda seemed to embrace it, questioning repeatedly in her works what it means to be a woman in Japanese society. Audaciously for the time, when Akiko wrote her name, she placed her family name last in the Western style, defying the Japanese convention still in place today of putting the family name first.

A product of these traditions as well as her childhood growing up in Hiroshima in the aftermath of the war, Chizuko has taken the Martha Graham technique as she learned it from Kanda and used it, as Kanda did, as a foundation to create her own expressive works that explore her own themes. And unlike Graham’s and even moreso than Kanda’s, Chizuko’s works often explicitly confront socio-political issues such as war and nuclear energy, topics that are ever front and center in power-war Hiroshima and often at odds with the foreign policy that the US State Dept had in mind when it sent Martha Graham to Japan all those years before. And even when Chizuko’s works are not topical, they often focus on the inter-relatedness of life and death and the existential question of how we live, and come alive, even with the understanding that death is always waiting, particularly in this era of mutually assured destruction.

Photo © by スタジオダンスコアポシブル Studio Dance Core Possible

Photo © by スタジオダンスコアポシブル Studio Dance Core Possible

Chizuko Kotani and Studio Dance Core Possible スタジオダンスコアポシブル performance of "There's Nothing Else Left" 「他にはなにも残っていない」at No More Fukushima! No More Chernobyl! Anti-Nuclear Festival, Dec 14, 2012

This time at UrBANDGUILD, she performed with 5-string fretless bass player and composer Hajime Totani. Although the piece, called “Live,” was improvised, she performed while trying to hold the thought of a person’s entire life and death in mind. Alone on stage at the start of the performance, Hajime played a series of wobbly droning tones. They sounded more like the product of a synthesizer than a bass, with cold and ominous overtones giving off a horror movie vibe. Hajime is known for his mysterious, ambient sounds and unique method of using multiple capos.

The audience alerted me to Chizuko’s entrance from the back of the house. Covered in a long red veil, she slowly undulated and gestured with her arms and hands, allowing the veil to loosen until it fell to the floor. Was she in the throes of grief?

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Hajime Totani at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Chizuko Kotani at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Chizuko Kotani & Hajime Totani at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Chizuko Kotani at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

Though now 71, Chizuko moves fluidly, each motion motivated by a clear intention. Seven years ago, Chizuko was interviewed by the Unforeseen Art Festival prior to her performance of her work“Blizzard” at the festival, and she told them that she was now ill. Remembering how her early teacher Miyoko Fujiwara had danced until the end, Chizuko said she hoped to do the same and die while dancing on the stage. I recalled that Chizuko’s other teacher, Akiko Kanda, gave her last performance just 12 days before her death from lung cancer in 2011. Fortunately, Chizuko is still with us, continuing to train younger dancers in ballet and modern/contemporary and dancing more expressively than ever.

She also leads and works with several other groups. P Company, made up of dancers from Dance Core Possible, performs a wide range of work. With WiSP (ア ウィスプ), she has been pursuing the performance project Seeds for Peace, her vision being, “Let’s spread the seeds of peace together.” On May 25th of this year, P Company and WiSP presented Chizuko’s “The Dropping of the Atomic Bomb” at Art Complex Hiroshima, fulfilling a longtime dream. Chizuko’s parents were both hibakusha, survivors of the atomic bomb. After the Chernobyl nuclear disaster occurred in 1986, Chizuko joined various projects to raise funds for disaster relief, and this work is but the latest of many Chuzuko has since created to bring attention to the dangers of nuclear war and nuclear energy.

Photo © by Chizuko Kotani

Photo © by Chizuko Kotani

Chizuko Kotani in first reading of "Chernobyl Prayer"

Photo © by Chizuko Kotani

Photo © by Chizuko Kotani

Chizuko Kotani and WiSP's "The Dropping of the Atomic Bomb" (presented May 24, 2024 in Hiroshima)

Photo © by Chizuko Kotani

Photo © by Chizuko Kotani

Chizuko Kotani and WiSP's "The Dropping of the Atomic Bomb" (presented May 24, 2024 in Hiroshima)

Miwako Inagaki's "Room"

Miwako Inagaki’s piece, “Room,” was a structured improvisation centered on the idea that she always feels trapped within the metaphorical “room” of the self and wants to break out. She said that each time she prepares to perform a new piece, “a storm is sure to come.” Her emotions begin to go up and down like a roller coaster as she struggles to create.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

"Room" by Miwako Inagaki at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

The process of creation makes her hyper-aware of always being “in the room that is me. I am wrapped, confined, healed, sleeping, and dreaming.” Yet, there is always the possibility that new inspiration will enter her mind and reshape her work and even her sense of self. “At the end of the day, I remember what happened that day, think of tomorrow, and fall asleep while being engulfed in a vortex of memories. I wonder how my room will be transformed. Will a me that is not me, a you that is not you, a place that is nowhere… appear?”

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

"Room" by Miwako Inagaki at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

I asked her if she ever felt that she did break through, and she said yes, many times on the stage. What is the key to doing it? “Facing yourself.” A teacher can lead you, “but you have to listen to yourself.” You have to recognize it for yourself.

Since 2013, Miwako has been studying with and sometimes performing with butoh artist Masami Yurabe, a founding member of the seminal Butoh group Tōhōya-Sōkai who has been making his own work for more than 40 years. Miwako goes to his lovely studio, which can also be a performing space, three times a week to work privately with him or take his small-group classes.

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

"Room" by Miwako Inagaki at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

"Room" by Miwako Inagaki at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

Photo © by Christopher Pelham

"Room" by Miwako Inagaki at UrBANGUILD FOuR DANCERS vol.281, Kyoto, April 16, 2024

She works part-time at a home next door to his studio, helping to care for people with disabilities. Besides being very convenient, this job requires her to be mentally present and work with various obstacles to communication and movement, which complements her work as a dance artist. Any resistance within her own mind becomes obvious, helping her to face herself and grow.

Growth is her goal—growth as a dancer, an artist, and a human being. She faces herself on stage and creates and shares work that explores, through movement and presence, the fundamental questions of who I am, why I am here, what might I become, and what might come through me. By doing so, Miwako invites audiences to face themselves and find their own answers.

0 Comments