KYOTOGRAPHIE KG+ Photographer Group “WOMB” (Masami Ueda, Rino Kawasaki, Kalina Leonard, Sana Kohmoto) 10th Anniversary Exhibition (April 26, 2024)

WOMB photographers Masami Ueda, Rino Kawasaki, Sana Kohmoto, and Kalina Leonard in front of the exhibit of WOMB magazines and photo books at their 10th anniversary exhibition at the Kyoto Museum of Photography

I had circled the KYOTOGRAPHIE KG+ Photographer Group WOMB’s 10th Anniversary exhibition as one not to miss. Among my many experiences at KYOTOGRAPHIE, it proved to be a highlight. Honestly, it was inspiring and rewarding beyond all expectations.

I was attracted to WOMB’s mission, which seemed to offer a feminine gaze yet take a metaphorical and expansive rather than body-centered view of a womb’s function. A small collective of Japanese female photographers who have been publishing WOMB photography magazine since September 2013, WOMB says they named their group and magazine to evoke “things that no one knows yet, a place where things are born (and grow).”

My first discovery came before I even entered the venue, the Kyoto Museum of Photography. Until I arrived, I hadn’t realized I had been there the year before. I remembered I had been walking around Kyoto to pass the time until my hotel room was ready. I had stepped inside a storefront to escape a sudden downpour and discovered it was a museum. At that time, the gallery was exhibiting candid photographs of various Showa-era members of the Japanese cultural Illuminati. I had since forgotten the name of the place. It’s a small three-story building with only two floors of exhibitions, and so I hadn’t remembered it as a “museum.”

Kyoto Museum of Photography

Upon entering the 2nd-floor exhibition space where the WOMB exhibition was installed, I was greeted by two young women, who turned out to be Sana Kohmoto 幸本 紗奈 and Kalina Leonard カリーナ・レナード, two of the four photographers whose work was being shown. During my entire time at KYOTOGRPAHIE and KG+, they were the only two participating photographers I met. I later learned that they were both based in Tokyo and could only be there a short time, so it was fortuitous that I happened to visit on a day when they were there!

It was not crowded at the time, but when I started to view Sana’s photos, I was nevertheless surprised that she joined me. Amazingly, I was able to view, describe, and discuss every one of her photographs with her, one by one. And then Kalina did the same with me. I’ve been to countless openings and met the artists, but I don’t think I’ve ever discussed more than a couple of the works with the artist. Usually, there are many guests to meet, and the artist doesn’t have the luxury to spend much time with just one, so I treasured this encounter.

But the most surprising and fulfilling aspect of the experience was that each time I described what I saw and felt about each photo, Sana and Kalina were, I think, both surprised and thrilled to find that I could look at what they had looked at and see it as they had. I asked if they had been doing this with visitors all day, and they said no, only with me. They savored the experience as much as I did.

Later, when I moved on to Tokyo, I reached out to them, and we got together to discuss their work and lives for several more hours. I feel we were each inspired and changed by the experience, so I’d like to walk you through some of their work and our conversations.

SANA KOHMOTO 幸本紗奈

unseen birds sing 個展

Although Sana and Kalina are young and not yet at all well-known, I found their works communicated their ideas in a way that was remarkably clear, despite the fact that none of them had a “message” per se. The brief statement accompanying Sana’s photos was more of a reminder to herself of how she wants to live:

Birds are singing outside the window.

I have never seen them singing, but they are there.

I still don’t understand the nods and winks – the signs hidden in everyday moments.

If I can, I want to gather sense and sweetness from the darkness – with a bit of expectation.

Perhaps this statement was also an invitation to others to join in her practice of seeing through artist’s/love’s eyes. I certainly felt my heart and curiosity opening in expectation.

Photo © by Sana Kohmoto

Photo © by Sana Kohmoto

Let’s look at one. At first glance, the contents of this one seem ordinary, a view looking across a street where no people or vehicles are present to a building with an external staircase leading up to what appears to be a gated doorway. A lonely tree in the corner reaches for the sun, not quite catching it in the play of light and shadow. I can’t see anything in focus, so I think Sana likely took this photo hand-held with a very slow shutter.

Hmm, why might she have done that? When I look at it, I feel there is something quietly mysterious, even mystical about it. The blur creates a softness. Even though nothing much is here, this lovely light is here. Just as she must have paused to take this long-exposure shot, I find myself pausing in this soft, dappled light.

And pausing here, I start to wonder who might go up and down those stairs. Do the building’s occupants also pause to enjoy this light, quietly bathing in the beauty of this otherwise seemingly unremarkable and unimportant location? Might they have even chosen to live or work here in part due to this redeeming feature? Are they lovers of beauty, perhaps painting away inside? Harried and weary workers for whom the moments coming and going, or stepping out for a quick break to smoke or call the kids after school, offer the only moment of respite in their relentless days? I can’t see them, but I can imagine them there in the before and after, hear the echos of their footsteps, unseen birds singing in the tree….

Sana’s approach reminds me of these words by Rainer Maria Rilke from his Letters to a Young Poet:

“If you will stay close to nature, to its simplicity, to the small things hardly noticeable, those things can unexpectedly become great and immeasurable.”

Photo © by Sana Kohmoto

Photo © by Sana Kohmoto

Here’s another one, a still-life of an apple, a common subject. But the apple is out of focus while the background is sharp. Was this a mistake?! Let’s assume it’s intentional. Why would Sana show a blurred apple? It appears to be on a little gold pedestal or coaster of some kind on top of a table or counter. Someone must have gone out of their way to display the apple there like that. In the background, we can see a partially open door, but the area behind the opening is pitch black. Hmm, my mind is more drawn to that.

There appears to be a black curtain draped over the top of the door, neither completely covering the doorway nor fully out of the way. Was the person who arranged it that way in a hurry? Why cover the door with a curtain? Is it a doorway to a photographer’s dark room, perhaps Sana’s own? To the right of the door, there appears to be a cabinet or appliance or something with an illustration of some kind on it. There’s not much else to catch the eye so the illustration, despite being mostly obscured by the apple, stands out. Except for the apple, it appears to be a completely uncluttered room.

By taking something familiar, a still-life of fruit, and using depth-of-field to draw the viewer’s gaze away from the fruit to the background of the image, Sana confounds our expectations. Confused, we pause and look again with eyes of curiosity, giving us the opportunity to take in something more, something new. In fact, artists have long depicted still-life subjects, not because they are obsessed with table-top arrangements, but because they can serve as a means of inviting reflection on how we see, how we create images, and how the techniques and attributes of representation interact with our perceptions to give rise to the meanings that we impart to images.

Just as in the previous photo, no people or animals are visible, but their presence outside the frame of the photo seems to be implied, invoked. This image also invites us to pause and wonder about who lives or works here, someone who doesn’t like clutter but who does value images and doing things with intention, someone who would think to arrange an apple on a gold pedestal to transform it into something aesthetically satisfying, perhaps an artist or art lover or Sana herself. Interesting. It seems that Sana uses photographs not only to get us to linger and reflect but also to stimulate us to imagine what is not visible and what came before. Being with her works reproduces in our minds something of the actual experience of a place and moment that she herself had. Photographs are flat, but Sana’s photographs immerse us in a four-dimensional reality as if we are mind-melding with her.

Photo © by Sana Kohmoto

Photo © by Sana Kohmoto

Let’s look at one more. What in the world? Did she take this one by accident? There’s just a big black shadow in front of what looks like a fence with some people behind it but their heads are cut off. Hmm. Is that a beak? Maybe it’s a closeup of a black bird? But it’s so underlit. There could be some feathers on the top of its head but the rest is pure black. No eyes are visible. Still, I’m pretty sure it is a bird. It’s not that sharply in focus. Is it inside a cage? But then why would the photographer be in there with it? It really looks more like a fence than a cage.

Even though I can’t really see the bird’s expression, I feel its presence. The blackness weighs on me. Fenced in, and obscured in the darkness, it feels solitary, lonely.

Since we can’t see the faces of the people in the background, it feels as if they are disconnected from the bird. Probably, they don’t even notice it. I feel much closer to the bird than to the people. Maybe the photographer has foregrounded the bird and depicted it in darkness in this way precisely to encourage us to think about its feeling, its point of view. What might it be thinking? Does it feel lonely? Does it long for other birds, perhaps a mate? For the disappearance of fences? Are there other birds around just out of frame that it can’t seem to get together with, or is it simply content to be apart for the moment? Sana said that, in fact, there were other birds nearby, but only this one was by itself. She, too, had asked herself these questions.

How wonderful that a photograph of what might initially seem like a “bad” photo of an unremarkable scene prods us to imagine what it’s like to be a bird! And a solitary bird behind a fence, at that. I don’t know if I would have paused to wonder what a bird might be thinking if I hadn’t paused to take in this photo.

“The function of artists is to keep people childlike in a positive way. To keep open to the world.” — Viggo Mortensen

Isn’t it also amazing that a photograph like this was able to provoke in my mind the same thoughts that the photographer had when she was there? In fact, each of her photographs accomplished this and revealed to me something meaningful that was unseen in the process. While considering all of this, I felt more energized and open, more playful, and when I think of it again now, I feel the same way.

Sinking into each of Sana’s photos with her, I felt that we shared something really deep and special. Sana agreed, telling me, “From the words that you saw and spoke with your eyes, I made many discoveries, and it was a very fulfilling time.”

KALINA LEONARD カリーナ・レナード

“Have You Ever Cried When Perfect Blue Sky Did Not Move You?”

I wasn’t quite sure how to move on from Sana’s work to take in Kalina’s photographs, but it seemed that Kalina understood what Sana and I had shared and was waiting patiently but expectantly, quietly excited to experience something similar. And the pointed title of her show, like Sana’s, prepared me to open to the deep feelings implicit in her images.

Consider why someone might cry because a perfect blue sky doesn’t move her. Perhaps, it used to move her, but now she can’t feel anything. What was beautiful or awe-inspiring no longer touches her. It’s as if something has been taken from her. She’s become numb. But she remembers that she used to feel moved and is aware of the loss of that feeling. And the awareness of that loss, whether provoking sadness or anger, moves her to tears.

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

Let’s look at one of Kalina’s photographs. It’s quite blurry! I think we are looking out a window on a rainy night. We can see drops of water and a film on the glass. On the left, there seems to be a multi-story building, offices or apartments maybe, with lights shining through many of the windows. I wonder what the people inside might be doing. To the right, the light is much brighter, but there’s no clear shape or form there. What could it be?! A glowing neon sign, or one of those buildings common in parts of Tokyo covered with enormous video displays? We can’t tell.

Something is out there, but we are at a remove from it, not only because we are on the inside of the window but because everything outside is so blurry. And while the rain would undoubtedly make the window less clear, I would say that what’s outside the window is more blurry because the camera focuses on the raindrops on the glass, and the depth of field is shallow. That is to say that the camera lens, which is the eye through which we are looking, has effectively been set to be near-sighted. We can receive the light from what’s in the distance, but we cannot render it clearly.

When I remember the title of the exhibition, I recall that it seems to refer to losing connection with something that once touched us. Is this photograph reflecting that experience? We can see something outside. We know it’s there, but we can’t fully take it in. Yet, we are looking anyway, outward, toward the light. There is some connection. It’s just interrupted, imperfect, distanced.

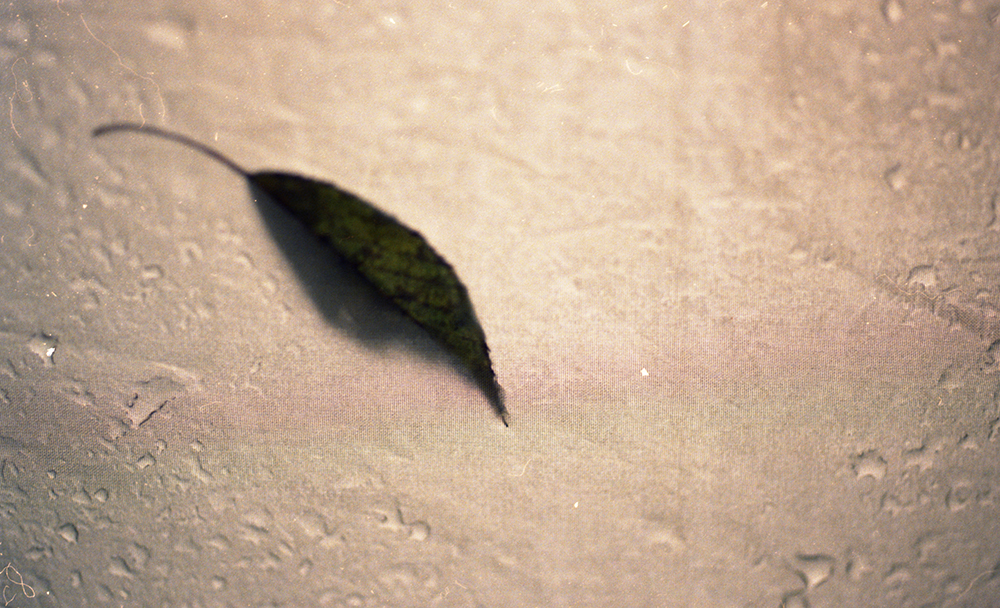

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

In this photograph, we see a solitary leaf resting on another wet surface, perhaps a sidewalk. The surface is beautifully illuminated with a soft white light emanating from outside the top of the frame, just to the right of center. We know that from the direction of the shadow cast by the leaf and by how dark the visible side of the leaf is relative to the surface on which it sits. If we looks clsoely, we can also see some lines and spots and streaks on the photo, consistent with the surface of a window. Perhaps, we are again looking outward through a window on a rainy day or night. I would venture that the light, by virtue of the direction, is again artificial, although possibly this was taken close to sunrise or sunset.

What do you feel while looking at this image? I feel touched by the beauty of the light and subtle richness of the texture of the surface. I feel much closer to the surface and the leaf than I felt to the buildings and lights in the previous photograph. I still feel separated by the window… but close, close enough to reach out and touch the leaf if I wanted, if the window weren’t there. It’s comforting. And yet, the leaf has fallen, and it’s alone. Do I feel fallen along with it? But we’ve fallen into this lovely light. My feelings are ambiguous. I feel connected to sadness, an ending, and yet the light offers me consolation and hope for something…beyond.

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

Here’s yet another one with a droplet of water. Here, it seems to be the focus. The image is sharply geometrical, with three almost horizontal planes of varying darkness at the top and an abstract, luminous area below. My first thought is we are looking at a partially open window with a window shade covering the pane that’s been pushed upward, and a single water drop from a rain shower outside is in the process of dripping down from the lower edge of the top opened window. Or perhaps the window is closed, and the droplet is on the outside, clinging to the the bottom of the top pane. It’s hard to tell.

What I observe again, as in the previous images, is a sharp separation between inner and outer, dark and light. Whereas in the previous image, a leaf had fallen, here a droplet of water clings (to the darkness) but appears to be getting ready to let go or fall (into the light). Metaphorically, this communicates to me a self-consciousness, a holding back and a yearning to let go, of being stuck in the dark but longing for the light.

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

Photo © by Kalina Leonard

Let’s look at one more. This one is entirely different! It’s a close-up of a man’s face held by a hand. It’s in extremely shallow focus, rendering the thumb and the nose in focus and the eyes and the rest of him soft, a little blurred. Placing the focus, the attention, on the thumb against the nose makes me feel self-conscious. Usually, when we caress someone, if that’s what’s happening, we don’t usually press the nose like that, do we? Do you? If I place my own hand over my face in this way, then my palm is against my mouth, like I’m wanting to prevent myself from speaking. It’s not really a caress. It’s kind of a tender embrace but also an attempt to limit the connection, as if connection is wanted but not wanted. The mouth and eyes seem to hang down, soft, not resisting but sad. The eyes do not look away or avoid the mixed emotions of the gesture either. They look directly out. One eye is more in focus than the other, echoing the ambiguity of the gesture. Overall, I get a feeling of “can’t live with you, can’t live without you.” Even though this image looks very different than the previous images, it actually seems to communicate something similar: a longing mixed with a holding back, a separation.

Kalia provided an extremely poignant and revealing statement with her photographs:

It has been a long time since my sight was blurred.

Rubbing my eyes won’t help.

Yes, I do see what is in front of me, But it does not connect with me at all.

No matter how I squint my eyes, Everything passes me by, and leaves me behind.

The beautiful landscape,

The light,

People who smiled at me and trusted me.

Too many of them have slipped through my fingers.

I had no control over myself;

I allowed depression to take me over.

But then I had a dream about a person who smiled at me once.

I said,

“Don’t worry, everything has become my flesh and blood.”

So, Kalina was depressed. She stopped being able to feel, to fully take in and connect with what she was seeing in the world around her. The blurriness and the separation represented by the windows in her photographs represent her actual lived experience. The man in the photo, who I learned was the primary subject of her photo book, was her boyfriend, whom she loved, but she could not experience that love fully because she was depressed. He, too, slipped through her fingers. But the light always remained in her mind, reminding her what was still there, outside of her reach but keeping alive the hope that she would recover. Like Sana, Kalina was able to clearly express metaphorically and visually what she experienced in a way that allowed me to experience it also.

Kalina told me that her father is a gay, very feminine American man raised by adoptive parents in Seattle. Her mother is Japanese and overly protective and controlling. They fought a lot and divorced. Kalina had a hard time but nevertheless appreciates her childhood, especially the gentleness that her father demonstrated as a man, and the kindness and love of her paternal grandparents. She realized at a young age that love is based on choice, not blood.

As a half-Japanese growing up in Japan, Kalina was bullied in school and grew up alone and lonely. She wanted to transcend her upbringing, not be scarred or determined by it. Wishing to grow and express herself and connect more with others, she took up drama in high school, but just when she was opening up, an abusive situation traumatized her and triggered her depression.

For a time, Kalina withdrew and could not go outside or interact with the world. To protect herself, she hid away her feelings. Taking photographs through the window became her way of engaging with the world from a place of safety. Rather than trying to convey any particular message or philosophy, she sought to express her mental state and continue to engage with the world to the degree that she could and find a way out of her depression.

Later, when she began to share her photographs, people told Kalina that the photographs captured their own depression. Some said that the light in her photos helped them to reconnect with their desire for recovery. The photos helped them to heal. Kalina had not taken them with the idea of helping others, but by working through her own depression and sharing that work, she realized that she was, in fact, helping others. She realized the value and power of her art, and she wants to continue. Today, as her work with WOMB and our two long conversations testify, she is able to function in the world again, to enjoy her life, and to engage deeply with others.

Kalina wanted to be in a band when she was younger, but she didn’t learn to play any instrument. Working with WOMB gives her an opportunity to be part of a creative team. The four current members collaborate to create the magazine without hierarchy. They decide on a specific theme, and then each creates her own work independently. Each of them responds to the theme in her own way. Both Sana and Kalina enjoy the process of being surprised by what the others create and being exposed to different interpretations or articulations of the theme. Sometimes, it is a little uncomfortable, but in a good way that helps them consider new perspectives and grow.

Sana says she had an unexceptional childhood and family life overall, but there were typical stresses and disagreements. Her grandmother was not always so understanding and sometimes became angry with her choices. Sana said she learned something really important from that. “When I saw her angry face, it was such a scary thing for me because I felt that it was a mirror.” Sana realized that her own anger was simply being reflected in her grandmother, and she didn’t want to have that anger. Looking at her own anger, Sana thought it stemmed from becoming frustrated that she could not express herself well. She wanted to become better at it.

She recalls fondly that her father loves reading, and she, too, developed a passion for reading as a means of self-reflection and self-development and connecting with reality in another, deeper way. Her sister encouraged her to be more ambitious and imagine a happy and fulfilling life for herself beyond the confines of their rural traditions. She said her sister opened her eyes to the larger world and supported her decision to pursue art.

Like many young creatives, Sana works multiple jobs to make ends meet. Her reading and creative practices have taught her to be curious about everything. She has learned to find inspiration rather than dissatisfaction all around her, including at her outwardly ordinary jobs. Her inner life has prepared her to explore and relate to the external world.

Later, I came across another passage from Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet that I thought spoke to her curiosity and determination to identify with her surroundings and find the wonder and life within:

“If your daily life seems poor, do not blame it; blame yourself, tell yourself that you are not poet enough to call forth its riches; for to the creator there is no poverty and no poor indifferent place.”

When I shared these words with her, she responded, “These words that Rilke wrote to a young man have saved and encouraged me also many times since I was young. I always carried a thin book containing Rilke’s letters in my bag when I wanted to concentrate on my works.” Writers like Rilke and Franz Kafka have shaped the way she lives.

Rilke, she said, described people as being absorbed and distracted by their thoughts due to their fear of death, preventing them from really taking in or understanding one another and the world around them. The artist’s role, then, is to undo or at least relax that thinking in order to experience the present and receive some inspiration that the artist can transform into art that may inspire others to have a similar experience. She also pointed out that Rilke expressed that it is difficult, if not impossible, to fully understand what a tree might be experiencing, much less a rock. But animals and trees and rocks cannot articulate what they are experiencing either. However imperfectly, we can use our gifts to attempt to express what they cannot, and in the attempt, we can come closer to experiencing our own truth. Artists like Sana and Kalina, like Rilke before them, demonstrate that there are riches all around us and that the key to recognizing them is replacing judgment with curiosity, with love.

In the interest of brevity, I won’t describe the works of the other two participating WOMB artists, Rino Kawasaki 川崎璃乃 and Masami Ueda 植田真紗美, in detail. But they also explored profound themes in simple and direct ways that were relatable and inspiring. And although they were not present that day, I felt their presence.

Rino’s photographs came from a time when her mother grew ill and died while Rino was pregnant and gave birth. They seek to convey the importance of living. She wanted to save her mother from dying, but her mother was more focused on living each day than on the prospect of dying. Belatedly, Rino realized that “we are not dying, but we are living,” and it is our thinking that determines which we seem to experience. She expresses how our perceptions shape our reality by overlaying a color photo of her son with a black-and-white filter and a black-and-white photo of her mother with color. This work invites us to consider what it means to live with or without “color” and examine how our needs and opinions might shape how we experience what we perceive.

Masami’s exhibition was born from the question, “What does it mean to live with someone?” and consists of “two photographs taken by the artist Masami and her partners (M and R), each holding a pinhole camera in a different location, simultaneously releasing the shutter, and capturing the same time period of a few seconds to a few dozen seconds.” It reminds us that even though we seem to be experiencing the same circumstances, our perceptions are always slightly different, even if we are extremely close with someone and sometimes forget we are distinct.

All four of these WOMB artists find / create images that conceptually convey something meaningful about their personal lived experiences or mindsets. I hope you can see that a whole world opens up when we observe closely, with patience and curiosity, as they do. We cannot, as Masami implies, know another’s thoughts and experience perfectly, but we can nevertheless open our minds wide and lovingly make an attempt to understand and achieve some communion. And we can create and enjoy art that brings minds together in this way. In the space opened up by these communions, new inspiration may arise, paving the way for further creations and communions. Curiosity and love make WOMB a fertile space for expression.

You can find WOMB online and subscribe or order back issues at https://womb.theshop.jp. While each issue mostly contains photographs, there is also text, including essays, presented in both English and Japanese. You can follow WOMB on Instagram at @wombmagazine

You can follow the WOMB photographers on Instagram here:

@kalinaleonard

@sanakohmoto_othermementos

@masami.u.photo

@rinodai

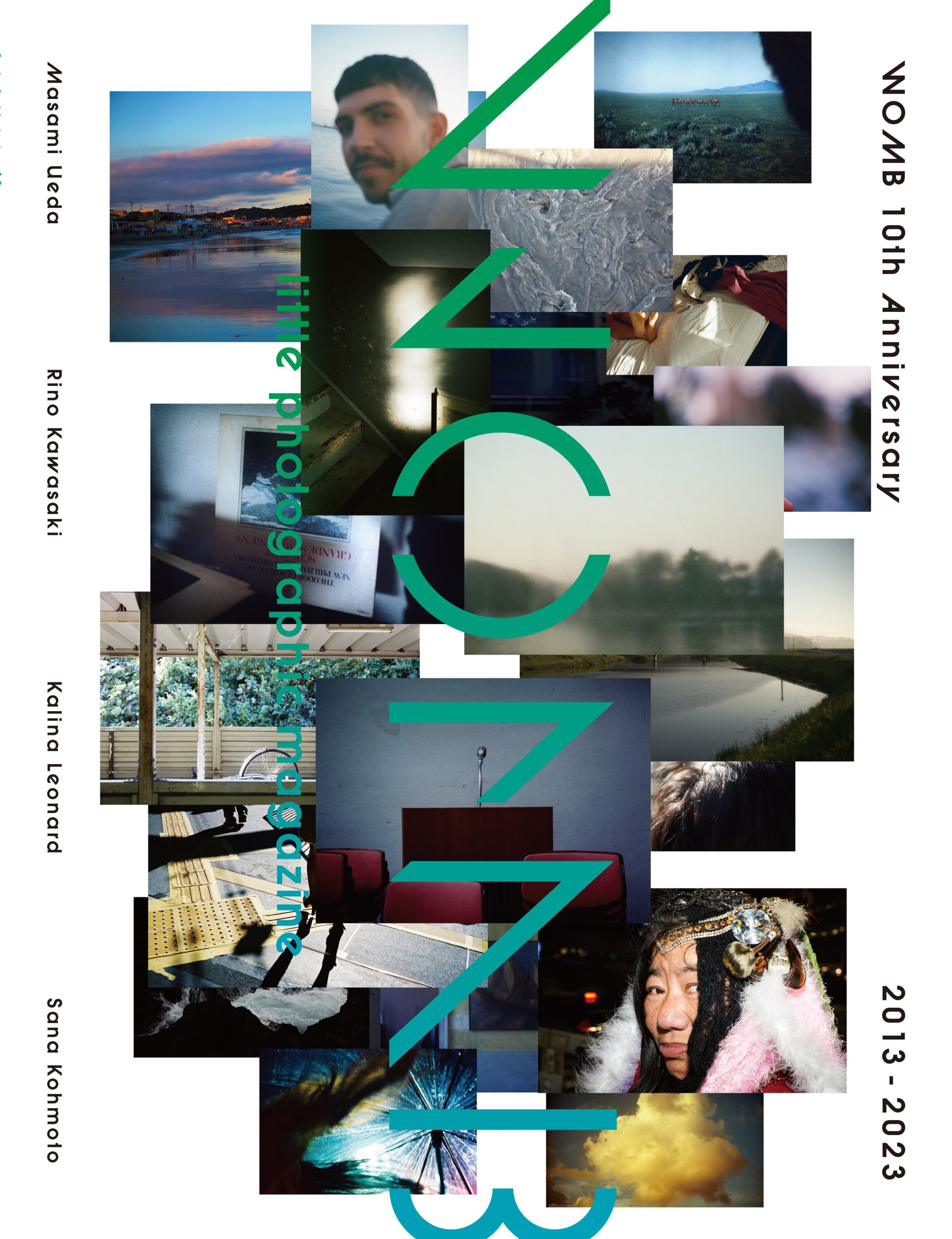

WOMB magazine 10th Anniversary issue cover

0 Comments